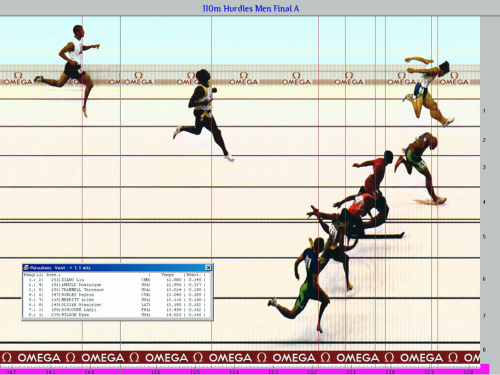

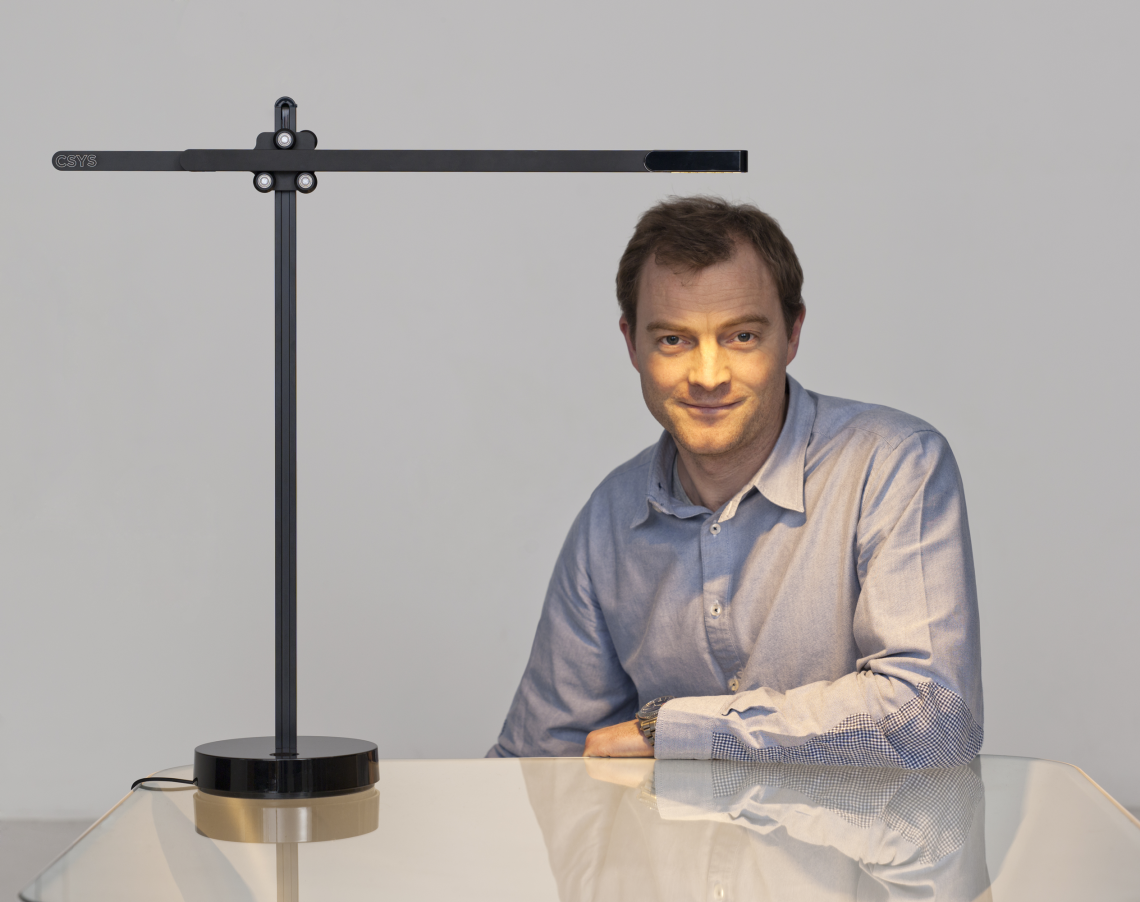

an interview with designer jake dyson. neocon 2012.

above> csys desk light

[DesignApplause] This interview took place during Neocon 2012 and we’re at the James Hotel with Jake Dyson. Jake, please tell us a little bit of your background and what you’re working environment is like?

[Jake Dyson] I studied product design at St. John Martin’s in London. The course was very aesthetic-based, all about styling. I actually made a water power generator that you attach to drain pipes in buildings so when it rains or you empty the toilet, it generates electricity and puts the heat back into the water system. The College thought this was a bit out of place, but it’s what I was interested in — moving mechanics.

I just did what I wanted to do and really enjoyed it. I patented that product. When I moved on from college to make money I found myself in interior design. But I wasn’t designing the colors of the wall or putting carpets in a space. I was making gadget-sensor-activated furniture, cabinets that opened by aesthetic or sensor tacks. It was quite interesting to work in this environment and it fired up my interest in product mechanics.

To be honest, I found designing for interiors quite boring because the tolerances are so great. You can have 5 millimeters gap here and there and it’s not critical. For product design and mechanisms it comes down to one-thousands of millimeter tolerances and that precision is much more challenging and exciting.

My next job was with product design office, Cock & Hen, Henry Slack and David Cock. One of their clients, David Linley Furniture, produced various products that required a fire blowing process and taught me about blow molding. One project was to make a blow-molded watering can with a watering butt and the tooling was very complex. It was that environment that I became interested in manufacturing and the processes evolved.

What I wasn’t learning was how you take a concept to the shop floor to manufacture and then sell it. So I took a backwards step and went to work for my father, which in my opinion, was one of the greatest training grounds for a design engineer.

[DA] What do you mean by backwards step?

[JD] It was important for me and my self-esteem to carve my own path in life. But if I really wanted to do that, I had to learn how. I felt the need to carve a self-made path on one end and at the other end was learn the extremely difficult path towards being a product designer.

[DA] Benjamin Franklin, a U.S. president and an inventor made famous by flying a kite in a lightning storm said, ‘Experience is the best of schools but only fools attend.

[JD] There’s definitely a fool in me. At Dyson I worked for 2 years with a team of designers and engineers taking a conceptual idea right through to the point of manufacture. I learned the process of experimentation, testing, getting things working correctly. That period also included computer-generated design and processes of manufacture. Although I can’t say I knew everything, it gave me a good feeling that I could go and do this on my own.

It was at that point that I moved back to London and found a very small garage in Wandsworth and started experimenting with a ceiling fan idea I had. It was a very mechanical clever ceiling fan that rotated around on the ceiling with its own reaction. There were two blades like a helicopter with one working the opposite direction of the other and it was bolt driven.

It was a strange fiscal phenomenon where one blade was fighting against the air against the other blade. The reaction of the main drive blade drove the system around the ceiling in a very controlled manner. I had created something I really didn’t really understand the physics of why it was moving in a controlled way. I got together with Professor John Whitehurst who happened to be the pioneer of the first-ever electronic washing machine. He was working for Bosch at the time and decided to come and work with me for 6 months.

We had to lean over this fan with blades going at 700 rpm, very close to our necks mind you, trying to understand the physics of the strange oscillations the fan produced. Whitehurst also designed a lawn mower, Flymote, which has a similar principle. When you cut the grass, the mower wants to go in one direction as it hovers. Both the fan and mower are extremely difficult to manufacture because of safety reasons and the level of testing and engineering required to take it to that level. I licensed that product and with that money, I set up my own studio in London.

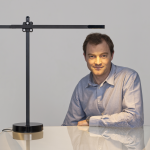

jake with the motorlight

jake with the motorlight

I also started working on a lighting idea from my interior design days exploring the limitations of lighting. People were up-lighting spot or flood bulbs and hiding them behind sofas or plant holders and they only could use either one or the other bulb. And it wasn’t a lighting piece people wanted to see in the roof. They were limited by the throw of light being either a narrow or a wide beam with no flexibility in between. I thought it would be fantastic to make a lamp which gave the function of all these degrees and angles of light, while also creating a beautiful piece you’d want to see in the room. I spent 2 years developing a focusing mechanism and the drive system. The Motorlight Floor launched in 2006 and it’s still on the market and in Europe, and Hong Kong.

Another lighting idea was to have an angle-adjustable wall light and I thought wouldn’t it be great if it was remote-controlled. These lights could be controlled and synchronized to create light sculptures on the wall and theatrical mood lighting as well. Again, another 2 years developing the product. That Motorlight Wall is also selling in those places.

The interesting thing about the second product is the use of main voltage halogen, which at that time was being targeted to be out-phased in countries because of the carbon footprint. Many commercial products were already turning their back on that technology. But during the development of Motorlight Wall LEDs weren’t right for the market. Just as I launched Motorlight Wall LED’s took off. I was caught between timing in the marketplace and transitional technologies.

[DA] What time period are we talking about? At this point in time the U.K. is controlling the kind of bulbs one can buy. When did the LED hit the marketplace in the U.K.?

[JD] LEDs have been around for 8-10 years in lighting products. They were initially invented in the 1960s in the U.S.

[DA] LEDs in the U.S. were limited to electronics indicator lights, holiday lights, most recently flashlights and automobile tail and running lamps.

[JD] Despite the limited applications people were pitching the technology to make them bright enough to be used for ambient and task lighting. A good 10 years of pitching.

It took a bit to truly understand an underlying problem. The problem was a loosely standardized chip manufacturing industry making it all but impossible to select consistent and specific colors of lights. When office buildings would buy a ceiling lighting system for example, the light color would be different on each unit. Also at this time the Chinese flooded the market with commercial lights encased largely in plastic with colors that might fade from pink to green. With all the poor offerings, it’s understandable how the folks were put off with the LED.

In the last five years or so the chips have improved and are more consistent and reliable. That’s why the huge boom in the LED lighting industry. But while that boom is great for the environment there’s a bit of a downside in the sense that in the race to compete in the marketplace too many of the LEDs were produced too quickly.

A bit like the fashion world with seasonal collections. There was not enough attention given to the science and technology behind how to make the product reliable and endurable which is important to the quality of light. It was more about quickly getting to market to sell at a right price or to make beautiful products people wanted to buy.

During this five-year period while working on one of my products, we decided to convert to LED. I’ve learned early on that you are unwise to skip an element of experimentation, a period that you have to do to discover the problem yourself before taking the product to market. You’re also wise to seek the advice of experts in the field so I flew to Malaysia to meet the head of Osram in Asia. I went to their new wafer plantation factory in Panang, where they developed the ability to produce a hundred million LEDs a week.

[DA] Why this particular company?

[JD] I recognized that Osram was creating very nice, warm white LEDs, a color temperature where demand outweighed supply. Interestingly, everyone was using white and blue LEDs because they wanted to falsify the brightness of the chip. The misconception, the whiter the light the greater the perception that the light gives off a lot of light

[DA] Is the warmer LED a redder light, the color temperature of the incandescent?

[JD] Yes, that’s the aim. As you know, in the UK the incandescent was taken away and there was the threat that halogen would be too. And the industry was getting concerned because the incandescent was the most desired color. Everyone was upset.

[DA] Is the desire for warm light mostly for residential? I would think a cool neutral light is more of a commercial temperature.

[JD] Well there’s a debate on this one. The cold daylight light was introduced to the office.

[DA] So daylight light is cold?

[JD] Well, artificial daylight is cold. Real daylight is not cold because the sun is yellow. Of interest, yellow is probably the first color you see when you wake up when you’re born. Daylight is also mixed with so many other colors, reflections from surfaces and objects around you. It’s not realistic for one artificial light source to replicate daylight accurately.

Did you know offices were using artificial daylight to keep workers awake later in the day, which isn’t natural. It’s ok in the morning, but later in the day you don’t want to be woken up. It’s not a comfortable working condition and there are better ways of doing it.

At this time the compact florescent technology was pushed by energy companies and governments to replace the incandescent light bulbs. In many cases, it was more about big energy companies wanting to increase their profits in a disposable environment. There is an argument that says the energy required to make compact florescent light has a large carbon footprint than making the incandescent. The fact that energy-saving light bulbs last for 10,000 hours is rubbish as well. It’s actually 2,000. There was a survey conducted in Germany where 70% of compressed florescent bulbs failed after 2,000 hours and reduced the level of light by half after 1,000.

Another matter is how uninformed and uneducated the public is regarding compact florescence. In the event of breaking one in your home, it’s advisable to put on protected eyewear, masks, open all your windows and evacuate your children and pets because there’s mercury inside the florescent.

Most of instructions however are directed at disposing compact florescence in commercial but not residential settings. There was an awful scheme by an energy company in England three years ago where they put four brochures in every letterbox in every house in England as a promotional stunt to avoid paying taxes. The government felt this was an incentive for manufactures to produce greener products and condoned the ploy.

[DA] So the government subsidized this?

[JD] No not directly and there was no government control policy and the energy companies made their own rules. Many compact fluorescents were made. Every household received four lights in their letterbox. Those who tried one and the first try didn’t give any light, most threw the other three in the bin. You can imagine four light bulbs for every house getting trashed and not enough knew the bulbs contained mercury. Obviously, a more informed public would have behaved quite differently.

[DA] Let’s get back to the quality of light. A better understanding of what you feel is good or poor light.

[JD] We can start with the shortcomings of the light bulb and what we have become accustomed to. We know that familiarity breeds comfort and that goes for lighting. The color in the lightbulb, which we feel is the desired color is pretty awful. The warm white is too orange and pink and makes everything overly red. At the other end cool white is too white and makes people tense, in some cases literally migraine-creating.

Not to mention the bulb is very bulky. The light fittings that have to accomodate the bulb are huge. The light emanating from the bulb requires reflectors to contain the light and throw it downwards. The net effect is bouncing light around objects to channel it. Whereas LEDs are very directional without much loss of light.

[DA] I’ve just become aware of the size of the bulb and the fixtures relative to the LED. Somewhat like comparing the 80s brick-size mobile phone with todays offerings.

[JD] Oh, much, much worse. All these happenings prompted looking back to move forward. My experimentation with LEDs and working with the head of R&D for OZRAM??, prompted the question, ‘How can you make an LED product last for life?’ His response was that you have to run the LEDs very, very cool. In fact, the optimum temperature for running an LED is -200 Centigrade. At that temperature, the LED can be powered with its maximum brightness for infinity.

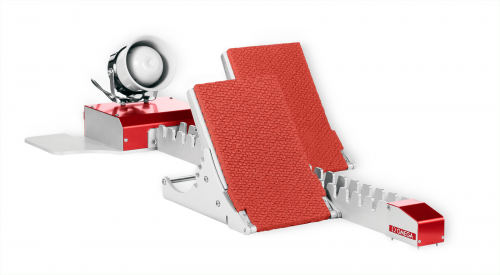

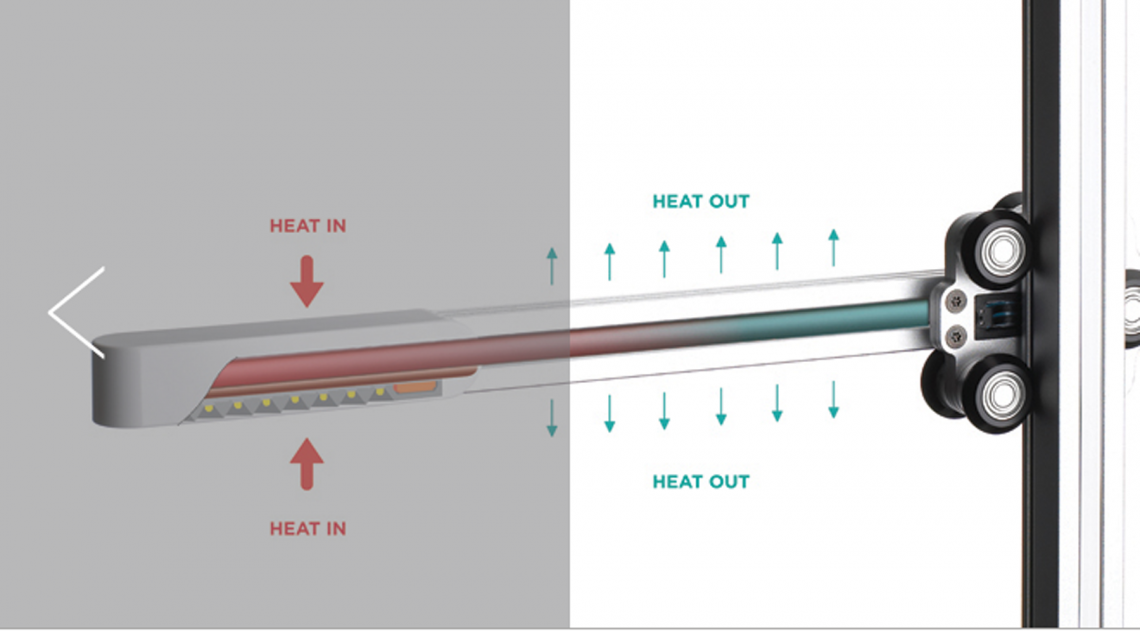

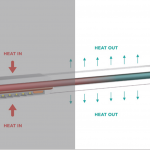

You can’t make desk lamps with refrigeration units. You would need compressors and gas. We did spend a lot of time on very complex designs to get the LEDs to run as cool as possible in our wall light. That’s how we learned LEDs are semi-conductors, an element used in computers. We bought loads of laptops from Ebay and ripped them to pieces to see how they were utilizing a semi-conductor. We learned the computer uses heat pipes to channel the heat away from the heat source and send it to the cooling fan. Fans are required in an enclosed environment, the computer body.

The LED lights that are not thermally managed properly start to change color. The reason, the LED in a light is actually a blue LED with phosphor on top of it and dyed to make the light white. If the LED is run too hot, the phosphor cracks up and the blue light filters through, mixing with the yellow of the phosphor. The light can also get a bit green and in some cases, a bit pinkish. In a commercial environment twenty ceiling lights can all be different colors after one year.

[DA] What is a heat pipe? A highly conductive metal?

[JD] No. Heat pipes were originally used in satellites. A satellite is -200C on the shade side and +200C on the sun side. Instruments inside of the satellite require a controlled temperature and it’s done by channeling all the heat from one side across the cold on the other side to reach a desired temperature. The heat pipe is a tube in a vacuum. You put a drop of moisture in water and evacuate the air, like in outer-space. The water in a vacuum boils at a very low temperature and vaporizes and shoots to the cooler end of the pipe. At the cool end, the vapor condenses back into moisture and by capillary action runs all the way down the tube to the hot end again. You have a cycle of vapor shooting via the center and moisture coming down the walls. That’s the basic principle of a heat pipe. It’s not new technology. It’s been around since the 60s, but it’s been refined and improved and literally under our noses in computers and servers. Its reliability has been proven. You’re more likely to see a failure in electronics than the heat pipe.

We took a box of cooling units and heat pipes to CCI Technologies in Malaysia. Amazingly, the parts in our box, they said they made every single one of them. I learned they were the biggest microprocessor cooling manufacturing company in the world and made units for Apple, Samsung, Hewlett-Packard and Intel and made 7 million units a month. They invited me to go to Taiwan to see one of their factories. It was a no-brainer to work with this company to develop a heat pipe cooling assembly for an LED light.

We designed my desk light together. It’s how we achieved an incredibly efficient cooling system. The light has been redesigned and now functions on the longest six millimeter heat pipe that’s taken to market. This breakthrough technology is designed specifically for me. It’s a great example of how you work with an expert to make something effective and reliable. The alternative is to throw in a heat pipe into a product without understanding how to use it.

above> jake with csys

[DA] Your light is more than just a pretty thing.

[JD] Absolutely. We don’t start with a sketch for a pretty object. We start from the reverse end. We experiment with chemistry sets and engineering. I built my own climate chamber room to simulate the effects of no air convection and to take heat readings in insulated chambers. We also ripped apart a few serious industry leader’s lights. Ripped them to pieces to see how effective their heat system is. We realized few were doing anything really refined. The common practice is overcompensating with masses of aluminium on the back of the LED chips. The aluminium gets hot cooking the chip. Most want to get the next product out. Our light took two years to design and test, making sure it’s reliable as well.

[DA] Can you say at this point that your light is unique?

[JD] Yes. I would say there are one or two other heat pipes used in LED lighting. I can say that our product uses the technology correctly, based on 25 years of computer experience.

[DA] Jake, is it ok to say it reminds me of designing a revolutionary vacuum cleaner?

[JD] If you’re trying to do something no one’s done before, you’re out in the wind. You could go in any direction. It’s not easy making new technology reliable and proving that it works. That’s what takes months and months and months. My father and their company, the technology being cyclone technology, are always working to make the products smaller and more efficient. This process involves a great deal of experimentation.

To give an example, we did try to make our own heat pipes with a product that sucks out air from a wine bottle to keep the wine fresh. But you know, it’s trial and error. And the product aesthetic detailing is last. Our desk light, for example, there isn’t one surface piece of material that doesn’t have a critical role. It’s completely refined and in my opinion, very, very sexy because being honest and showing the workings of something can be intriguing and very, very exciting. When you’re using a product and it’s performing well, it’s always going to be a satisfying experience.

[DA] How long do your products last?

[JD] We have a five-year manufacturer’s warrantee on a product. I really wanted to guarantee the LEDs for 37 years. But what happens if our plug unit fails and our customer on the other side of the world says the LEDs don’t work anymore. I can’t determine whether it’s the plug that failed or something else. I’d like to say, and you can take my verbal reassurance, that the LEDs will last that long.

[DA] The new LEDs coming out for consumer use to replace the incandescent carry guarantees of 18-25 years. The LEDs are at the mercy of the hardware. Are they just taking a deep breath in order to quickly grow a market?

[JD] Here are two thoughts. One is the 18-25 years are benchmarked on seven hours of use a day. My quotation of 37 years is based on 12 hours use a day.

Two, manufacturers who supply the LED chips may state a chip life of 50,000 hours. They know their chips are going into products that are running way too hot. The truth, an LED can have 220,000 hour life or longer if you run cooler. But they say 50,000 hours.

Right now lighting specifications are very misleading because everyone is measuring their products by a different standard. Someone can tell you that a compact florescent has the same light output as a 50-watt halogen or that an LED replacement spotlight has the same light output as a 50-watt halogen though you can barely read with the LED spot. The reason is the light level is measured in the beam of light, not in the overall light given off in the room. They’re allowed to make these claims under current non-standards.

[DA] You mention the different light temperatures that occur during the day. One color when you wake up, another by the time your are ready for bed. Is there merit to a bulb that is one color in the morning and changes color and makes you more relaxed at night?

[JD] Probably but at the same time, it’s very subjective. Everyone wants different things with light. I mean it’s like genetically modified food. I don’t know how much we should tease our eyes but I did see something very, very interesting. I don’t remember the source but it was a fish tank. A company was tuning LEDs to allow the algae and plants in the fish tank to stay alive but never grow. So you don’t have to clean it or cut the weeds.

[DA] Possible?

[JD] It’s possible, I think. It is interesting. You notice how greenhouses are being switched over to LEDs and I bet it’s not just about energy use.

[DA] Genetically modified food through light.

[JD] The produce that has been grown under sodium lights may just be different than produce under LEDs. I’m not going to make an adjustable light which one week puts me in Hawaii and another in London. But it’d be interesting to see the reaction if another company gave it a go.

[DA] I was supposed to interview Ross Lovegrove in Milan, but it didn’t go through. But I did a bit of research on the both of to you. Do you talk to him?

[JD] We’ve never had the opportunity to chat. I’ve met Ingo Mauer several times. We’re two very different types of designers.

[DA] Any other lights you can talk about it?

[JD] We’ve launched a much larger version of the desk light for the floor so it’ll tower over sofas and chairs, but has the same technology, movement and articulation. Just a bigger, more wonderful light.

You know, there’s legislation now coming to place. Quite a few office buildings are taking out overhead lighting because of its servicing and energy consumption. It’s headed towards more localized lighting. What a fantastic time to be doing task lights! Good timing for a change.

[DA] I was talking to an ergonomist and his company was building furniture and task environments in such a way that it improves the well-being of work over a long period of time. It seems obvious that the lighting plays an equally important part.

[JD] Yes of course and maybe someone should be developing a mindset for a longer living light source. I’ve concentrated on making an LED product last for life. Everyone should approach light design that way. We’re now seeing disposable LED light bulbs based on the assumption that commercial premises have a refit every 7 years despite that specifiers are willing to accept 30,000-50,000 hours life on a LED downlight fitting. A well-designed interior, including light, should have a long shelf life.

That’s the whole point of sustainable architecture. And I was being slightly rude about the Hawaii/London lighting. The color of light is absolutely important. It may be my hatred for compact florescence and white light that has driven me towards a product with very nice warm white light. And the realization the marketplace is not worried about losing the light bulb but losing the color of light that comes out of it. And the realization that some bought beautiful lights in the 70s or 80s and don’t want to stick compact florescence that looks like there’s a Mr. Whippy Ice Cream coming out of the front of it.

[DA] You’re achieving a bit of sustainability just by the longevity of your light. That’s a statement. Make sure you have a date stamped on your light.

[JD] Actually, that’s a very good idea. There is a serial number on the side. There is a lot of movement at the moment where people are using the volume of recyclable material in their product as a marketing point. I’ve seen one or two products that are almost entirely CNC aluminium, a key marketing point that their product can be recycled. We have lot of completely refined aluminum extrusions. We could recycle it. But there’s a very small quantity of plastic which is absolutely essential. You have to have plastic in things. There we go.

[DA] Jake, is there anything you want to say that we didn’t talk about?

[JD] Maybe restate that there’s one other similarity with Dyson and that is that we design a product, engineer it, test it, market it, manufacture it, and sell it all ourselves. We’re not a business that designs conceptually and hands it over to another company to produce. We do everything ourselves. We oversee a company in Malaysia and all of the supply chain. The quality of how things are made. Within a small design company, that’s quite unique I think. This model is critical as it’s the only possible way to maintain pure quality control.

peanut | miki astori | driade

peanut | miki astori | driade