Art in the hamptons. Parrish art museum.

click > enlarge

click > enlarge

We decided to visit the new Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, near Southampton on Long Island before the season started. This came after a week when the Museum of Modern Art announced its decision to destroy Todd Williams and Billie Tsien’s Museum of American Folk Art building after only a few years.

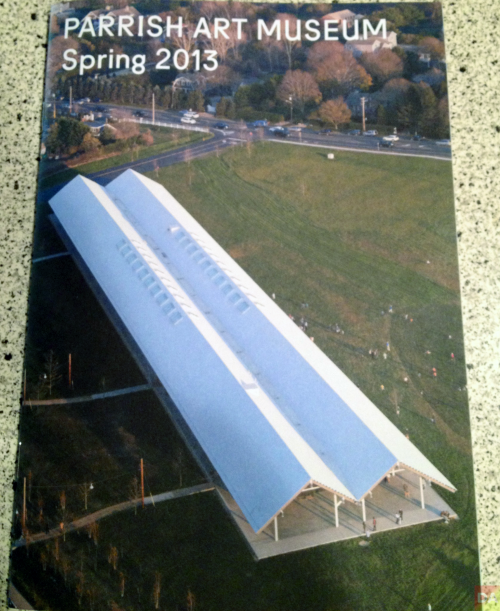

The contrast could not be greater between the two art museums: the forty-foot-wide building on a townhouse lot in the city and the long barn-like structure sprawling across a vast fourteen acre pasture on a road outside of town.

The Parrish is the work of another dually denominated firm, Herzog and De Meuron—actually, more a collective or team than partnership and a Pritzker prize winner.

It makes a striking first appearance, glimpsed from the almost rural road, an immensely long silver stick stretched out in green grass. (Silver is how the corrugated tin roof and bare concrete at first read to the eye.)

As the visitor approaches, the building comes more and more to suggest the agricultural buildings of the area, notably the barns of the potato farms. This was of course intentional. But its long double roofs, to many Americans with rural experience, will suggest the shape of chicken houses—not what Herzog and de Meuron had in mind. “Our design for the Parrish Art Museum is a reinterpretation of a very genuine.

Herzog & de Meuron typology, the traditional house form,” Jacques Herzog wrote recently. “What we like about this typology is that it is open for many different functions, places and cultures. Each time this simple, almost banal form has become something very specific, precise and also fresh.”

The big sheltering roofs also echo the feel of the landscape in the area: the huge sky dominates the flat fields with few structures or trees to break the horizon.

The building is constructed from a hierarchy of materials, from informal and impermanent toward their opposites, from top to bottom: corrugated metal roof with skylights, bare timber, steel I beams and finally concrete walls and floor slab.

At first the concrete walls seemed excessively strong. But they already look like ancient stone and they ground the impermanence of the lumber and steel above, turning the vernacular forms into more ambitious, “high” architecture.

One of the failures of the Folk Art museum was its entrance: it was hard to find and far from welcoming. Oddly, the entrance at the Parrish is problematic too The visitor approaches a large glass wall which appears to welcome, but it has no doors. Instead, the entrance is to the right in a dark wall. Is this a metaphor for (or joke about) the exclusivity of the Hamptons? Or a metaphor for the difficulty of entering the world of art by head-on thinking?

The two roofs join at a point that covers a central hall, so the roof framing joins in an X theme above visitors’ heads. The space is remarkably flexible, with temporary walls; large lobby like spaces alternate with closed galleries. The variety of spaces are useful but the visitor has little guidance; a promised mobile phone app or printed map will be needed. The space planning is highly practical given the face of art today, the range from performance to video to installation and mega sculpture.

The museum had been located in a prissy and forbidding Italianate mansion downtown in Southampton before moving to Water Mill, 2 miles away. The design for the new building originally envisioned an assemblage of studio like buildings but was radically rethought after the recession crippled fundraising. The result may be better; it is certainly less pretentious.

This area—eastern Long Island—was the location of the original Big Duck, the duck shaped concrete building that sold ducks and the area is full of basic buildings—sheds, often covered with shingles, the duck’s opposite in Venturi’s pairing, the so called decorated shed. The two joined structures of the Parrish are undecorated sheds but carefully detailed ones. The door handles are one off, sculptured rods. Some clever architect the in H & de M office devised a untreated wooden bench structure about ten feet square, for the galleries. Clever pocket doors close off the shop when it is closed. Benches cast in concrete run along the length of the north side. The roof extends beyond the walls, covering a wide walk and a whole outdoor gathering space. Thanks to the visible wooden beams, this provides a suggestion of traditional Japanese architecture. It is also going to make the place a terrific rental for weddings and the fundraisers that during the season tap wealthy local sojourners.

After looking at the Parrish’s size and generous rooms, we sat in the café, on the chairs Konstantin Grcic designed specifically for the museum. (Review: tough on vertebra.) Thinking of the Folk Art museum, I thought: how mad it seems to think of trying to build a forty foot wide museum! I almost thought it might make sense to bring the whole folk art collection here, with galleries to display it.

The Parrish’s collection is grounded on holdings with local tradition: the Impressionist William Merritt Chase, who set up a painting school in the area and the realist Fairfield Porter. But the area was home and second home to many abstract expressionists and Pop artists. De Kooning, Chamberlain and Lichtenstein to name a few. Up the road a few miles is the site where Jackson Pollock wrapped his Oldsmobile around a tree. A growing collection based on local traditions is sure to benefit from the proximity of part-time residents and visitors among collectors as well as artists like Alice Aycock, whose show is opening next week.

You might think of it as a vacation museum—its barebones construction might be taken as the informality of the second house.

<a href=" about phil patton

about phil patton