Connecting dots: an interview with izzy+ founder chuck saylor.

neocon 2012 | click > enlarge

neocon 2012 | click > enlarge

DesignApplause asked Chuck Saylor at NeoCon 2011 for an interview, after all, it was his company’s 10th birthday. A year later we opt for a visit to izzy+ headquarters in Spring Lake, Michigan. There is much more substance when you visit someone’s “home.” What was served up to this visitor (me) was a medley of creative vitality and mellow conversation. [DesignApplause] do you think creative people live longer, or maybe they are productive at what they do for a longer period of time?

[Chuck Saylor] An interesting start to our conversation. I do have an opinion about that, and not because I have any special kind of insight. But if you look around the world, creative people last longer. And it is not uncommon to see great artists, photographers, writers, architects going strong well into their 70s and 80s and continue to be very strong until something physically or mentally happens.They don’t really hit their stride sometime into their late 50s. There’s a lot to be said for creativity as a way of lengthening our life.

I just interviewed someone who had spent time with Peter Drucker in California and said that in his personal library there was a shelf of his books, which he had placed there in order of their publication date. The shelf was the full width of your arm span. Drucker was quick to point out that he was 30-something when he wrote his first book, and between this spot and this spot was when…when he turned 65, he had gotten to about the fifth book and then the great majority of those books came after he was that age. That’s when he had all the acquired wisdom.

When I first met and spent some time with Frank Gehry he would have been in his mid-to-late 50s, and just coming to great public prominence. He was well-known in a lot of circles, but in terms of his global impact, his own brand and work that he did, you look at how prolific he has been in his 60s and 70s. It’s pretty phenomenal.

And growing lots of great young talent around them is another really interesting characteristic of these creative people. As they get older, they don’t keep it all to themselves. A handful of people do that, but, for the most part, they’re giving that away and helping others find it while encouraging and supporting them to help perpetuate it for all the right reasons. They’re engaged with one or two generations behind them. I’m sure they would all say that younger generations help inspire them and keep them going, as well.

[DA] I can think of reclusive geniuses who don’t seem to need anyone except maybe a new mistress every now and then. And I’m not implying that genius only resides in men, but, interestingly, there’s no contemporary name for the equivalent of a female’s mistress. But yes, being around young people is a source of energy and a conduit to new ways to do things. My students more than anything else persuaded me to learn how to text.

[CS] I agree with that whole heartedly. It’s extremely important. Not only because what you can give to them, but what you gain from their insight. If you’re 70 and can tap into that, there’s an energy and a learning process that greatly benefits the older person. I think that’s why all the great masters always had large groups around them that were all younger like Frank Lloyd Wright and the great industrial designers from the Modernist movement from the 40s and 50s.

[DA] When did izzy start? What year?

[CS] We launched in 2001. The idea started in early 1999.

chuck saylor

chuck saylor

[DA] Chuck, as izzy’s founder, let’s talk about you and how the concept of izzy came up, tell us about your background and how it serves you.

[CS] I’m a furniture brat, Ron. Since my early 20s, I only had one other job outside of the office furniture industry. My undergraduate degree is in mechanical engineering and I studied industrial design and art. I wanted to be a painter and my father thought that was silly. He was an automotive guy. For him, being an engineer was a much better job. He didn’t think being an artist was a really good idea. So I went to work for a really interesting gentlemen here in Michigan named Ed Prince, who was an automotive guy. A mechanical engineer, actually. He started me in the back room in the mechanical engineering department.

We made large aluminum die-cast machinery. It what was just sort of mind numbing work for me. About two years into it, he sat down with me and changed my life forever. He was a really tremendous experimenter and encouraged us. We experimented with all kinds of things like one-man helicopters. He was an inventor and a creative engineer. He said, ‘You know, we have you in the wrong role. You need to be much more of a designer or an artist. You should be working in furniture or something else. We’re never going to fulfill what you want to do.’ I said, ‘Are you firing me, Mr. Prince? You know, I’m 22-23.’ He said no and to stay as long as I want, just that I was in the wrong place.

It was about six months later that I got a phone call from a recruiter who was looking for a design and engineer-type person for a small company in Holland, Michigan, by the name of Modern Office Modules, also known as M.O.M. There was a young engineer who was in charge of parts of the business at the time for his father named Dick Haworth, who I interviewed with. I was in a large group of people who interviewed and was the youngest and least experienced of everybody. We had two or three really terrific interviews and our thinking was somewhat similar in terms of research, risk taking and experimentation. He ended up hiring me and my job was to start with a clean sheet of paper and work with him in developing a power-panel system, which we would eventually do and launch in 1976 at NeoCon. So that started my love affair with the furniture industry. I got into it when Haworth was less than $4 million dollars in sales and I got to know a lot of people my age. The industry hadn’t found itself yet. It was a wonderful right place, right time opportunity for me. I fell in love with the industry. It let me be me. At a very early age, I was able to fulfill all my internal ambitions and dreams.

I’m a big connect-the-dots kind of guy. I’m constantly looking at multiple data points and reading a lot and talking to many people. So for me, the industry took a huge chunk of our society called the work place for the future and we had the sudden confluence of technology coming and changing things. If you looked at my generation, and at my father’s and grandfather’s generations, and now here comes the early Baby Boomers who essentially didn’t want anything to do with those earlier generations. To be at that place at that time was an unbelievable experience, in my opinion. We were able to do research and look at all these dots around me that were changing tremendously and that was just fantastic. I loved every minute of it.

I would go to Silicon Valley before there really was one and meet people my age who were thinking about working, technology, and the built environment. We would sit, have coffee and talk about the future of work in Palo Alto. To be honest, to be in this environment and having no experience you wonder why am I even there. A real reason why I was there was was because Mr. Haworth, Dick’s father, was a school teacher before he entered the business, and so he really valued learning. He wanted all these young people around him to learn and grow. He gave us the freedom to do that, which was awesome. In my lifetime, one of several really great life lessons came from that experience. I learned a lot from Dick’s father and his example.

I stayed in the industry with Haworth and then had a chance to go to work for Bobby Cadwallader at Sunar, though it was Hauserman at the time. We had our first child and I told my father I was moving to Cleveland. He thought I was completely insane. The river was burning the year I moved there. What a wonderful experience because, while I loved what I was doing at Haworth, there were a lot of other dots I wanted to explore and connect, which I couldn’t do there. Mr. Hauserman, along with Bobby who had just left Knoll, had it in their heads that they would build another Knoll. They purchased Sunar from the Sunshine Biscuit Company in Canada.

With that I met a person who I would come to value tremendously over the years, another young designer with many ideas, Doug Ball. Doug and I watched all the same movies and read the same books. Another designer now involved was Neils Diffrient, who was building a studio in Norwalk. During that summer we got to connect lots of dots, experiment, and challenge the status quo. Race came out of Doug’s work there. Neils designed a next generation future system we actually prototyped with Xerox, which has been forgotten. But if people saw it today, all the lights would go on. Everyone would say, ‘Why don’t we have that product today?’

It was really a brilliant product at the time and had technology integrated into it. Bobby introduced us to a lot of really great people that I admired — Richard Sapper and Michael Graves). Bobby brought MG in to design showrooms. We worked on a project called Mainstreet with Doug, which is still in my mind today, two or three steps beyond what DIRTT ended up being. It was never produced, though a lot of people wanted it. Then I went to work for Knoll, who acquired the rights to it. But Knoll was going through big changes at the time and they never did anything with the project. In 1990, Westinghouse Electric acquired the rights to Knoll and I got to connect another whole bunch of dots in that process.

In 1996-97 time frame, I was just tired to be honest. My first granddaughter was born. I was living in Chicago working for Knoll. My wife and I wanted to be closer to our grandchildren when they came. Knoll was now coming back together and I was traveling about 70-80% of the time.

[DA] What were your responsibilities at Knoll towards the end of that chapter?

[CS] I had been internal at Knoll in New York and East Greenville, in marketing and design with Carl Magnusson and Andrew Cogan. I ran product marketing for a while and then I was also included in design at the time with Carl. Then we decided to decentralize the front end management of Knoll into five big geographies where each area had sales, marketing and distribution. I became a divisional vice president and that was the last job I had at Knoll.

[DA] Chuck, a big regret of mine goes back to 1991, when I met you. Every time we got together you were like ‘Let’s do a book on Knoll, Ron.’ Did you ever do one?

[CS] No, no. But in many ways, the very best, most meaningful time of my life was at Knoll. It was the culmination of the most important learning phase of my life. For me I was with some of the best people on the planet. Well-educated, hard working, committed, passionate about design, the legacy of Knoll…there was a time when certain people would have given it away. It was a miracle that the brand survived, and it is because of the people willing to stand in front of the bus at the time and say, ‘We’re not gonna let it go.’ That to me, speaks volumes of the people who were there. I get asked a lot and, quite honestly, I ask myself a lot of times, ‘Why did I ever leave?’ I love that place and the people. The day I resigned, I had all my peers and John Lynch, whom I love dearly and don’t think that anyone could ever give enough recognition to what he has contributed to the saving of Knoll, tried to talk to me out of it.

You could spend a lifetime just studying the people side of Knoll and its history as well as being inspired every day by those people and their contributions to a single place. I decided that we would leave Chicago and I moved to Grand Rapids. I went back to being an industrial designer.

ready for izzy 10th birthday party at neocon 2011

ready for izzy 10th birthday party at neocon 2011

[DA]This was 1996?

[CS] 1997. I thought I would just go be a consultant. I had a number of nice accounts and relationships. I was busy and I wanted to be under the radar. Honestly, by the end of 1998, I was bored out of my mind. I started thinking about the future of work and there were a lot of things going on in the world at the time that were unsettling. You could sense that some fairly significant change was on the horizon. If you’re constantly thinking about connecting the dots, what’s amazing is that when they come into alignment there are ‘aha’ things that you see. All of a sudden a half a dozen come into alignment and then your mind is like, ‘Oh my goodness. Something serious and significant is going to happen.’

A lot of things I’ve researched, studied and written about all revolve around these defining moments in our history that are led by crises, technological change and design. Design plays a significant role in them. You had the dot coms, the unraveling economy, the early thinkings of globalization and the sameness that had crept into our industry with work-station cubicles. This next generation of young kids were being born and were growing up in a different world. I started thinking about where my granddaughter would work and what she would do.

I had a couple of good friends who were big Apple folks and we would spend evenings thinking about the future and the nature of work as well as portability and miniaturization. What’s it gonna be like? That kept bubbling around in my head and I said, ‘Somebody needs to be thinking about this. I think there’s a business model I can create to look into this and start creating places where this next generation can work. Those characteristics would be a place where hierarchy would go away and not be as important.’

My generation grew up when power and position were everything. I could see that beginning to change. I was intrigued by taking a look at places and products that would have to support this new wave of a much more collaborative, interactive and less hierarchical place to work. I had no idea what that would be or what it was about. That was the basic premise of the start of izzy. I named it izzy after my second granddaughter Isabelle, dedicating the thought process to her and the day when she would be ready to work. She’s now 13. My objective was to work on places for that generation to feel comfortable to interact and work together.

We started on that journey and launched at NeoCon in 2001. I started the company in August of 2000. I wrote a business plan and shopped that around while trying to find partners. I didn’t want to manage a manufacturing operation. I felt like there was so much capacity in the world that if I could find people good at that, I’d leverage that and said that I didn’t want to be the back-end guy, but the front-end guy. It happened that I met a family business in West Michigan led by a young guy named Nelson Jacobson. The company was JSJ, a corporation based here in Grand Haven. They were primarily automotive based and industrial brands.

They have six different businesses. I met them working on a project for Haworth. I gave them the business plan in August of 2000 and they agreed to fund the startup of izzy and I went to work for them. We started on that whole premise of creating mobile, interactive, collaborative workplaces for future generations. JSJ had purchased a company in Texas called Superior Seating and they didn’t know quite what to do with it. Nelson had a couple of ex-Steelcase guys running it and they asked me to go down and look at it. At the end of the day, part of the deal was that we were going to roll that business into izzy. We did that. Then we launched in 2001 and then 9/11 hit three months after. Thankfully, they stayed right with me in support and said we’ll get through this. We did. JSJ’s been phenomenal as owner and very supportive by letting us do what we wanted to do. Never imposing. They’ve been incredible .

One of the big things I saw in the connecting of the dots was that brands were going to become much more powerful and important in the future. In some cases, more important than product. While today we all recognize that, in 1999 that that wasn’t necessarily the understanding. You would start with a cool product idea and build up to where you had a brand. We started izzy concentrating on creating new products but also putting big emphasis on building a brand.

I said to people that I wanted to build a brand just like I’m building a product and I wanted to build a brand just as fast, and to have specific meaning and purpose. I wanted to build that public awareness of what izzy stands for and believes in, doing everything we could to stay true to that. And we’d build around it so the brand would come first and everything else would come after.

[DA] Was your vision then at the time the brand and idea you have now?

[CS] Yes. In May of 2000, I did a Powerpoint slide for the JSJ board that had the izzy brand and hovering around it were other brands. Part of the brand strategy was that if we could create a strong enough brand awareness, we could pull other brands into the marketplace with us. So we wouldn’t have to be all things to everyone with one brand.

That multiple brand strategy came from the very beginning. At the time, I had no idea how difficult it would be. We began working on messaging and the imagery of izzy from day one. That it would be highly differentiated and we’d create this interesting, quirky, fun, different kind of voice. There were many great companies at the time. We wanted to create a brand that everyone would be interested in listening to. Telling a story became the second biggest part of our branding strategy, which would lead to printing our own storybooks to tell our story.

valentine’s day 2011

valentine’s day 2011

[DA] You turned the company into a person. Someone that you would like.

[CS] Yes, very much so. That’s what we tried to do. I had followed people’s work around human-centered design and it just resonated with me. I adopted many of those principles in everything we did. That humanness around design became a very powerful driver for me and still is today. I think that voice of a company being a person with all the imperfections of a real person became a powerful driver for what we wanted to do. I hope that that honesty and authenticity still resonates. We work very hard on being approachable.

People should be transparent. That has been the vision for the brand since the start and we’ve just continued to work on it while dodging all the bullets around financial crises and the recession of 2003-2004. And then in 2006-2007, we had grown the business and the brand was getting some recognition. In some circles, people would say that they really like the brand but didn’t know what we do. We clearly had an awareness bigger than what we were. Lots of people would talk about us the negatives of that issue and I would say, ‘Yes, that’s exactly what we’re trying to do.’ It was never a short-term plan for me.

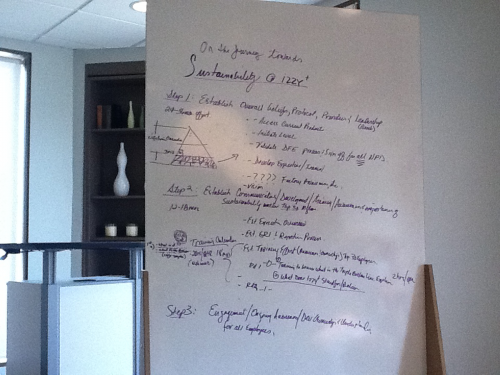

It was always a long-term plan for me to create a business that would have sustainability for future generations. We experienced decent growth. The JSJ folks were incredibly supportive. The board in 2007 said to me, ‘You’ve got organic growth happening, but it seems you have a stronger brand and the ability to have faster growth through acquisition. Why don’t you start taking a look?’

So we did. We interviewed people and created a list of brands we’d like to acquire. The criteria was about strong brands. We started looking and asking our independent rep firms what other brands in a perfect world would resonate with the A&D community that we could acquire and that would add value.

At that same time, on our new product development calendar, we were pulled into higher education on custom projects. We’d done a couple of university projects and I talked to administrative officers at several different universities. The same thing I felt in 1998-1999 about corporate America, I found talking to presidents, provosts and other senior people in universities. There was an uneasiness in higher education in 2005-2006 that was palpable when you got there. Kind of an aging professorial group, not really adjusting to what was a pretty significant technological change that would impact learning. This structure around hierarchy that everything inside of you would say it isn’t right for the future. They were all saying the same things but were struggling with what to do.

The classroom became the focal point of that discussion. Is the classroom for the future really right given the movement, the coalescence occurring between pedagogy, space and technology. Will these three elements of learning come together in a more meaningful place and way — and how? I saw that as a huge opportunity for the future. While we started to look at acquisitions, I connected with a young industrial designer that I’d been watching for a couple years prior to that — a young man from Grand Rapids named Joey Ruiter. I said let’s go out and research the universities and talk to as many people as we can in the A&D community and in the university community. Let’s start thinking about building a product line for the future of learning in the classroom.

[DA] What year was this?

[CS] 2006. In 2007, we started looking for the acquisition. Part of the criteria was not only strong brands with A&D recognition, but also if there was an institutional brand out there that already had brand awareness in an educational sense. In November of 2007, we got a red book from an investment banking group selling a company called Jami. Jami owned Harter, Fixtures, and some other lesser-known brands. But Fixtures made all the lights go on.

Harter, too, was a great old brand and I had known the Harter family. They had a strong emphasis on Modernism in the early days and on good clean design. They also had a good brand name and needed help. Fixtures had completely wandered around but all its heritage came from the education market. Perkins & Will were rebranding Fixtures for the future. It’s one of those wonderful things when all the stars and moons line up. In December of 2007, we flew to Kansas City and I met the team and the ownership.

The third criteria for the screening process was finding a way to run izzy the business. I came back to the organization and said, ‘We’re growing and getting more complex. There are days when I’m the CFO, the manufacturing guy or the marketing and branding guy. Designing the products. I can’t do it all.’ I had all these young professional people I brought into the company, but no seasoned senior leadership on the management team to help with the operational side and infrastructure of izzy. That’s clearly neithert my strength nor my passion.

I called the Jami team together. There was Greg Masenthin, who is the President and Joan Hill, the Chief Operating Officer. They’re both in their late 40s at the time. They were exactly what we needed and I loved the brands of Fixtures and Harter. In January of 2008, we started putting something together and by May we had an agreement. In June we announced at NeoCon the acquisition of the Jami group and their brands for izzy. The leadership team is still intact today. Greg is now the President of izzy+ while Joan is the Chief Operating Officer. We launched izzy+ in June of 2008, doubling the size of the company and getting some really outstanding people at the same time.

With everything public and in place here comes the new product we’re working on for higher education called Dewey. Instead of giving it to the izzy brand, we put it into the Fixtures brand. It helped redefine Fixtures back to its heritage in the institutional educational market, which has been really successful for us. We’ve continued to add new products.

All of our product development effort is focused on these product brands that have very specific product application functionality tied to them. Instead of squishing everything into something called izzy+, we kept all the brands separate and with very specific application targets for what they do. If something is redundant, is in a place it shouldn’t be in, we’ll put it someplace else or get rid of it. This strategy has proven to be a really great opportunity for us. It was much harder than anticipated but we’ve done it. The consolidation, the internal branding, the repositioning.

[DA] I know the brands are distinct and special and they are all “family” so to speak. How autonomous are they?

[CS] They’re not. They’re all together. We created two big buckets of activity, one on the manufacturing side.

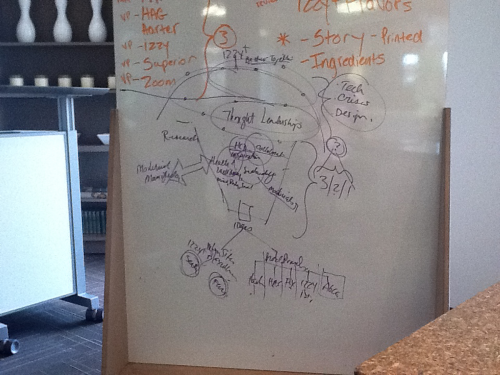

What we did early on, was create these different buckets. One bucket is the we call “Thought Leadership.” Inside Leadership we have Collaboration, Sustainability, Health and Well-Being, and Human-Centered Design. The Leadership bucket is where all of our research is focused. We’re trying to get deeper and broader into these topics.

Human-Centered Design recently has been distilled to one word: Inspirational. What inspires us when it comes to a built environment? Health and Well-Being asks questions like: Can we create products that support people being healthier, a big conversation around mind, body and soul.

[DA] These buckets, these conversations Chuck, do they derive from the universe around us or are you going after these things and creating the buckets?

[CS] I think they’re swirling around us all the time. These elements are the dots that I’m trying to connect.

buckets and connecting dots | during interview chuck brandishes his blue marker

buckets and connecting dots | during interview chuck brandishes his blue marker

[DA] Your juggling dots.

[CS] Right. The deeper you get and the more dots get connected, the more you see the inter-connectedness with all of these and life around us. We spend a lot of time thinking about, researching, writing about social media. This is where I spend half of my time. As these dots connect, we then we move on and hopefully create products and branding information that support it.

For example, from the Thought Leadership area, ideas form and are captured under an umbrella called izzy+. That was the best way I knew to describe what all of this is about. Today on the front page of U.S.A.Today there was an article about peer-to-peer sharing and what happens when we share and leverage through social media to make us better at the end of the day? I am reading Bill Bradley, one of the really great minds of my generation, a Hall of Fame basketball player, a Rhodes scholar, and a senator, an amazing combination. His new book is ‘We Can Be Better.’ It’s really a thought-provoking manifesto.

izzy+ has a tagline: Better Together. Our over-arching quest as a brand is we are better together generating ideas, then products, then pointing the products to what I call manufacturing sites of excellence. We started with a Fixtures factory, a Harter factory and an izzy factory which made furniture, some seating and some trying to make it all. We’ve collapsed and consolidated five places into two manufacturing sites of excellence, one around seating and one around furniture.

In our manufacturing site of excellence in Middlebury, Indiana, we take all we know about how to make any chair at any price-point in the most efficient way possible at one facility. We can make a $2,500 leather HAG H09 executive chair all the way down to $150 task chair out of the same site. And then in Florence, Alabama, we have 400,000 square feet of manufacturing space, which is where all of our furniture is made. The space is literally is cut in half. One half is metal working, powder coating and welding. The other half of the facility is saws and laminating and building wood things.

There is no individual brand tied to any one of these manufacturing sites. When you drive up to the plants, they are izzy+ manufacturing sites of excellence. Our product brands are Harter, HAG, Fixtures, izzy and ABCO. Harter concentrates on conference rooms and private offices. HAG does high-performance task seating. Fixtures is any and everything that has to do with learning. izzy is all about first space and day-to-day task seating. ABCO is modular laminated case works.

webster | fixtures

webster | fixtures

[DA] Please tell us what you mean by ‘first space’.

[CS] We divide up this work and ideas tied to these brands into 3-2-1 –3rd, 2nd and 1st space. 3rd space being a Starbucks cafe, 2nd being a classroom, 1st space being my space. We’re concentrating on products that support the values of each space. I do believe over time they are coalescing into a new space yet to be defined. This has now become our model of work and how the product brands work.

Most recently at NeoCon 2012, we are now consolidating and delineating in a much better way than ever before. We’ve been working so hard at the consolidation and integration of everything from operating systems to sales reps. It’s been a big journey since 2008. I anticipated it could take us five to 10 years to get it all done until September 2008 happened. I started laughing when Lehman Brothers went bad and someone said, ‘What the heck is wrong with you?’ I said, ‘You know, if you need a crisis, just have me go do something around launching and something really significant will always happen.’ I’ve launched Izzy in June 2001, right before 9/11. Now we make this acquisition in June of 2008. September 2008, the financial markets crash.

It’s been interesting. The good news is the people side of izzy has survived and thrived and done a lot with very little. That’s the powerful story. The people side of the equation is the most important and continues to thrive and grow in the midst of all this change.

Now in 2012, I think society has hit a tipping point. It’s taken us as a society a decades, since 9/11, for an intellectual transition to occur and I’m not sure we’re fully through it. In this time globalization has become a central idea. There are still more things trying to connect. This whole conversation on what’s the future of work and learning is around a much more connected collaborative world. We’re concentrating more around simplicity and sustainability. We’re not talking about hierarchy or control, but giving it up and what that means. Also, a product portfolio that starts to answer all those questions that drive this change. These dots get driven by technology, crisis and design. If you look historically for a thousand years before us, these three issues are always the leading drivers of significant change. We’ve been in the midst of it for sometime. In 2012 we come out of the old mentality. We’re never going back again. It’s a very different world going forward.

[DA] It’s interesting to listen how you incorporate an urban planning concept of home, workplace and community into your model. The 3, 2, 1 space-build concept helps you focus on what you’re doing and now leads you into thinking about the potential of connectivity. The end user, are they aware they are connected somehow or is it even important to be aware?

[CS] It starts with us. To me, there are two key things. One is back to storytelling and it starts with our people. They need to understand the story well and buy into it. Two is that the storytelling from all of us transfers out. You’ve got leading change agents and laggards coming behind them. Our message helped to differentiate us. This is concept selling so you have to be able to tell that story. What do we mean by 1st, 2nd and 3rd space? When we get into that discussion, I think that resonates with people.

[DA] It’s an inclusive discussion.

[CS] We now see people talking about the working lounge and these creative cafes. What is that all about? When you look at 1st space and 3rd space, over the last two to three years the difference between what is going on in these two spaces is getting less and less all the time. They are gradually coming together. So here comes something called “benching” that has quality of worklife and collaboration on the one hand, and lower cost, smaller footprint and cheaper for customers on the other. I don’t fall on the right hand side, but I do on the left hand side because it gets at the heart of this formula.

One of the challenges the industry will deal with is that in the future world we are going to have to solve these issues. It isn’t going to be an $8,000 workstation solution. The cost structure will be different. Technology and transparency and how we interact and communicate with one another will be different. It will be a smaller footprint. Much more meaningful and important work has to be done. It’s going to be cheaper but more powerful because the work is not going to be driven by process but by people.

connecting dots

connecting dots

[DA] What does sustainability mean to you right now?

[CS] When I started izzy, I had a simple phrase, ‘I don’t want to add to a landfill.’ That is a good place to start. We’re still on that journey. It has now expanded dramatically so that much more of our time is spent on the social responsibility side of sustainability in terms of communicating to our people and getting them engaged on the topic. I’m a big advocate of LEED and BIFMA Level and the efforts that the industry put forward. I think it is a multi-attribute effort that puts a lot of accountability and responsibility on the manufacturing side to do the right things from a sustainability standpoint. We’re deeply into that as is much of our industry today. I think our industryprobably leads the world in many ways on the sustainability equation.

[DA] We were Milan this past Spring. We noticed a few manufacturers building things in a much different way. Where most cabinetry has always been heavy and very durable, new materials were surfacing. The objects were no less durable but lighter, the build more efficient. There were even companies offering to buy back the product so they could recycle it. Unfortunately the new way is more expensive than the old though once volume kicks in the price should come down.

[CS] There’s been a wonderful thing subtly occurring. I think if you get to the Modernist manifesto, time, technology and materials are finally arriving. When we talk of sustainability, materials make up one of the biggest areas we look at. Everything from recycling materials into our existing products. As an example, the product we showed at NeoCon that won the gold medal is the Nemo Trellis product. You can use recycled materials all over that product.

Creating a framework that you can take materials and recycle them into something else inside the built environment is a part of that, too — all the way from hunting, researching and finding new materials that are out there. What’s exciting is that there are many people in different places doing advance materials research and new materials that are just popping up everywhere. I think materials is a huge component of this discussion and we’re at one of those exciting periods of time where we will see huge strides made in sustainable materials.

Ron, you visited our showroom briefly in Chicago. Did you see izzy+ flavors?

[DA] I did. Please tell us about that. Also, tell us about what your customers are looking for.

[CS] I think if you take a look at the A&D community, they’re looking for simple and intuitive things. That’s a big topic for the design community. Materials, as well. We’re selling to them a broad range of products from seating products, lounging products to a broad line of different kinds of tables, and it represents 60-70% of our business. We don’t do panel systems or those kinds of work stations. That’s a big chunk of what they are getting from us.

That would be on the working side. On the learning side, higher education, it would be things like Nemo and Dewey, which have been very successful for us. We have things like lecterns and marker surfaces to flexible desks and tabling. Simple, clean, rich, recyclable materials.

We all know that price is a big component. Too many people want to rush to ‘it’s price’ and then give up on everything else on the assumption that the consumer is only buying price. On the assumption of buying price, I think that segment of the marketplace is dwindling. That’s probably counter-intuitive to a lot of people.

I guess the cynic could argue that if we had broader bandwidth in price, maybe our volume would be bigger. That would be a fair argument. We’ve tried very hard not to be drawn into that. In the products that we had, like the ABCO business, they had been positioned around being on the lower end of price. We’ve actually tried very hard to add more value from a design and product standpoint. I can see that in that segment of the marketplace, the consumer is very sensitive and very aware of added value. Also willing to pay somewhat more for it.

[DA] I hear this quite a bit lately. People are making a big effort to buy things on price only so they can own the things that are really near and dear to them.

[CS] I think in this world that’s evolving, buying objects, things that people love and want to keep forever, is becoming more and more important. I can see that. I see that in my children. Even in my grandchildren. They’re much more discerning about what they really want or like. It has to be something that is going to last for a very long time. They don’t want to throw it away.

[DA] The answer to sustainability sometimes is durability, making fewer longer lasting objects. What izzy wants to provide is longer lasting.

[CS] That’s back to the design conversation and materials. On our higher education product line, we interviewed facility managers and that was their number one issue. When we first got there, there was culturally a common issue that was furniture. Students are tough on furniture in classrooms. It just doesn’t last long. We emphasized in our design brief that we needed to make this indestructible and we built it so it lasts a long time. It’s going to be more expensive than buying a cheap table from China for a classroom. But we found the market. They appreciated the fact that it was being designed to last for a long time.

The cost-first syndrome to buy the cheap thing is not necessarily what is going on in the marketplace right now in terms of higher education. It doesn’t mean that they are not discerning buyers or getting competitive bids. There is greater value being placed on better design and better materials. More sustainable and lasting longer.

nemo bar and arc | izzy and harter

nemo bar and arc | izzy and harter

[DA] Tell us how NeoCon operates in your business. I can see the housewares, even kitchen and bath, where all the buyers come in and all those things go into department stores and venues like that. How does NeoCon work and how did it work this year?

[CS] It’s a very hot topic right now for me. I think the most important question that should be asked is what are we trying to accomplish at NeoCon? As silly as that sounds, I think it’s a very fair question. I’m not sure that we are all in agreement with what that is. Can you possibly show enough product? All the product configurations for someone? We all know the answer to that. No way. And if you start on the 11th floor, by the time you get to the 3rd floor and walk out, if you remember all the products you saw on the 11th floor, God bless you.

We should be asking ourselves: Do we think that there’s an opportunity to have meaningful dialogue with our customers. I don’t know that we get nearly enough opportunity or chance to do that at NeoCon. To me, that should be the number one reason why we have it. It’s to connect with a well-educated and well-communicated A&D community, who know the industry, all of us, and how to access the Web which gives them great photography and access to great information and specifications. But do we get enough time to sit with the A&D community and have meaningful discussions with them about trends and what is and isn’t working?

A large show like that, you would hope, might accomplish that. Do we get a chance to put our best thinking forward at NeoCon? Sometimes, perhaps. But we’re all so consumed with getting showrooms ready and spending an extraordinary amount of money getting ready for what turns out to be two to three days.

I have a lot of questions about what we should really be trying to accomplish at NeoCon. On the positive side, do we put a good face on the industry? NeoCon isn’t the industry. It isn’t owned and isn’t controlled by the industry either. It’s owned by MMPI, not by the contract furniture industry. NeoCon itself gets some brand awareness. Our individual companies do, too, as a result of it. At a major industry event like that, I would prefer seeing our industry get more brand awareness.

[DA] Is there a voice out there other than NeoCon that does get your industry brand out there?

[CS] If you define the industry today as we know it, maybe using BIFMA standards, the answer would be no. Not that I’m aware of.. The businesses do a very good job at their own individual brands. I would be surprised, though, if there are many A&D customers coming into that building who aren’t already well aware of most of those brands. We’re not drawing enough of the actual end user into NeoCon. We get customers who do come with a dealer or design firm, but not as many as I would hope we could get there. To me, it gets back to the question of what exactly are we trying to accomplish there and are we getting to a place where we can build a stronger customer relationship? That’s one of the most important things NeoCon should be trying to accomplish.

[DA] No one has the energy to sit down and come up with an answer to your question, right? You’re attending because everyone is there, but it could be something better.

[CS] I think it absolutely is worth asking the question. We should all put a lot of time and thought into how to make it more meaningful. I’m of the mindset that I wouldn’t be trying to pass judgment on it based upon how many people come or don’t. I’m interested in if it’s the best foot forward given the role and responsibility as an industry we have in America’s learning, our healthcare industry and the working environment in our country. We play a very significant role in the culture of institutions all over the world. I personally think we should get a lot more recognition as an industry than we do now. It’s a fair question that all of us should be asking. Are we really accomplishing what we would like to get done for the industry at this show?

[DA] Has NeoCon changed since 1976?

[CS] I think it’s very similar in a lot of ways. I would ask, is it still culturally relevant? In the early days, you were looking for recognition and trying to build brand awareness. It was an industry that was just starting then. There was a lot to do. Now we go into this new period of time where the industry inside itself, inside the A&D world for example, is known quite well.

[DA] I’m fond of putting all kinds of models in the pyramid shape. With the exceptional 10% at the peak. Is the really good stuff in your industry the 10%?

[CS] If you looked at our industry and pick a number. Let’s say it’s a $10 billion industry in North America. It could be bigger or smaller. Some very good, well-run and designed organizations control 60-70% of the industry. In that definition alone, I would say it’s a lot more than 10%. I think the customer who buys from our industry gets one of the best deals in America. The value they get, when you think about the testing that goes on, the view of health and safety within our products, the design input into our products, the manufacturing ability, the story of sustainability, recyclability, recycled content that’s embedded in many of our products today, the likes of historical giants like Herman Miller and Knoll on the product design standpoint, Haworth, Steelcase, you look at these businesses and you would have to say realistically, you could not make a bad decision buying product from any of us in this industry.

That group, at least 60-70% of contract office furniture that gets sold in North America, gives the marketplace an incredible value. I don’t think you can say that about all industries in America, but in this one, I would say the customer is the winner. Hands down. Even when offshore products continue to come in, they are trying to live up to that product design standard that’s been set by American-based companies at a much lower price. They get there, maybe not always through lesser materials, but through lesser labor content, lower overhead, government support, I mean there’s a whole myriad of reasons they can deliver a really nice task chair to America for a fraction of what one of us can. Those imports that abide by our industry standards benchmark deliver tremendous value to the customer base here in North America.

[DA] Your customer base, is it primarily U.S.?

[CS] Yes. 99%. We make it and sell it here. I think there’s a lot to be said for globalization and manufacturing and delivering to specific markets. There’s a lot to be said, as well, for design made and sold in America. I’m extremely proud of the fact that we’re an American company and entrepreneurially driven. Fully 90% of what we do is designed, built, assembled and sold right here. We have attempted to go international. But it’s always because a design firm has specified some of our products for offshore. Not for any other reason.

[DA] Chuck, is there anything we haven’t talked about that you’d like to get off your chest?

[CS] I obviously am passionate about our industry and izzy+, as well as its future. I hope it is going to continue to have a very special place in American business as well as in the contract office furniture industry. As I said, I truly believe that the real winner in our business in America is the consumer. This is an industry that delivers incredible value for the dollar. Not surpassed by many other things.

[DA] Could you do that chair book now? At this point in time?

[CS] I could, I could. One of the nice things we get to do because we don’t have a huge legacy, we get to start with a clean sheet of paper and to look at everything that’s been done and figure out a new and exciting way to do it. We have a new chair that we’ve been working on for two years that will launch next year I’m really excited about. It’s a definitely a game changer when it comes to task seating. It’s driven by these four big buckets. One of the newer products has all four of those from the very get-go embedded into the research. I am really excited about that product.

[DA] We can’t wait to see it. Your designer and partnership, are you outsourcing it to any other designer or are you keeping it really close?

[CS] Actually, I now am only advising, supporting, counseling and mentoring on the design side. We do it all externally with independent designers. What I’ve tried to do is build a family of designers who know us well. Whenever we have a need, we can create a brief and give it to that group while feeling very confident that if it fits within what their interests are, that we’ll get a great response back from them. Every time they have an idea, they have a place to bring it to. They know how we work. We work in a very digital world and at a pretty hectic speed and they are comfortable in that. We have a group of designers around the world that we work with all the time and can be with this organization for a very long time.

[DA] Chuck, a wonderful discussion about buckets and dots. Thank you. [ izzy+ ] [ izzy+ flavors ]