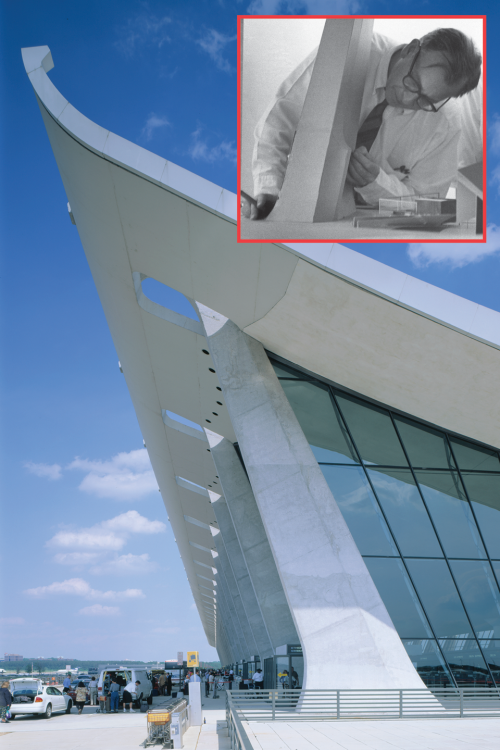

Chicago architect Thomas Beeby, FAIA, is awarded the 2013 Richard H. Driehaus Prize at the University of Notre Dame and becomes the prize’s 11th laureate.

Credited with helping to bring traditional architecture and classical city design back to the practice during the 1970s and 80s, Beeby co-founded the Chicago practice HBRA where he is currently the chairman emeritus. He is a graduate of Cornell University, where he received his B.Arch., and he received his M.Arch. from Yale University. After graduating from Yale, Beeby returned to Illinois to start his practice.

Many say traditional and classical architecture was ‘reborn’ in 1976, when the travelling exhibition One Hundred Years of Architecture in Chicago was to be shown in 1976 at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. The show focused largely on Mies, his predecessors and followers, that it distorted the historical reality. Four local architects simultaneously mounted a counter-show in the Time-Life Building which attracted nationwide attention. With the addition of three more architects, Beeby included, the group became known as the ‘Chicago Seven‘. The feisty group introduced a fresh spirit of critical engagement, one which recognized that talking, and thinking, are every bit as important as building.

[ driehaus prize ]

The following may best describe the ethos behind this prize:

Traditional and Classical Architecture and Urbanism

Twenty years ago the curriculum was reformed to focus on traditional and classical architecture and urbanism. It is worthwhile to reflect for a moment about what those four words mean.

Classical architecture is the best that a tradition produces. Every culture has a tradition. Ours runs from ancient Greece and Rome through the founding of the United States (think of Jefferson’s wonderful buildings) and on into the present.

Urbanism is the counterpart to architecture. In training our students to be leaders in the profession of architecture, we must equip them to build and improve our cities and rural areas. In a well-designed, livable city, the public realm complements the private realm, and not all buildings are classical. Indeed, most are good traditional buildings contributing to a complementary public realm (think of Rome). We therefore teach our students how to work with the appropriate national, regional, and local traditions of urbanism, architecture and construction. What works in America won’t necessarily do well in Panama. What is right for Boston is not right for Phoenix.

Rejecting tradition or launching a radical transformation at its expense as occurs in most other schools of architecture ill equips a person to use his or her God-given gifts to make the built world a better place for everyone. Such an education deprives a person of the inexhaustible fund of experience tradition makes available for guiding leaders. Tradition is much broader than classicism. Classicism is only the narrowest, highest peak of achievement standing out above the broad plain of tradition, an inspirational example of the best to be sure, but an isolated peak nonetheless. No plain, no peak. We can live on the plain, but a peak is a rather narrow roost.

— Carroll William Westfall

Past chairman and Frank Montana Professor, University of Notre Dame School of Architecture

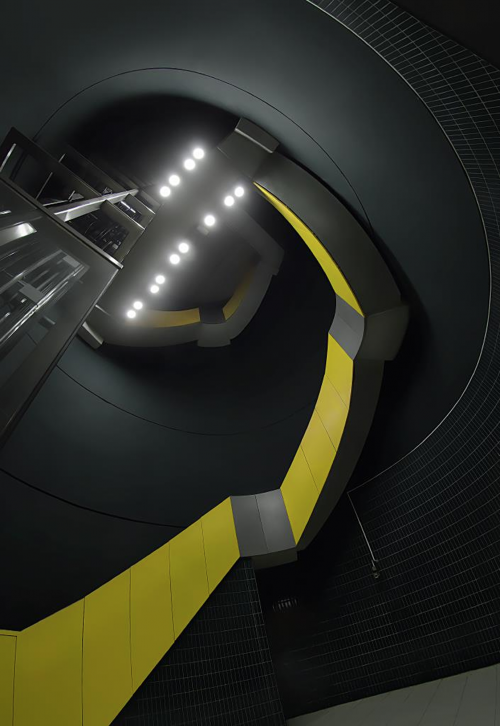

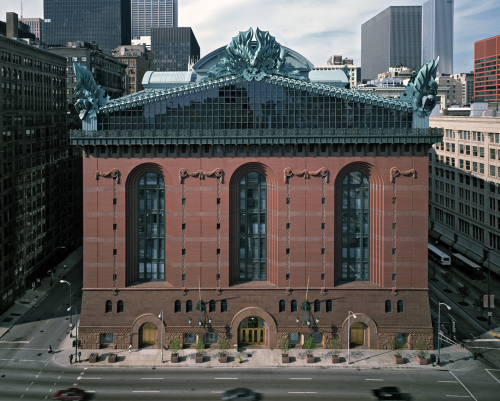

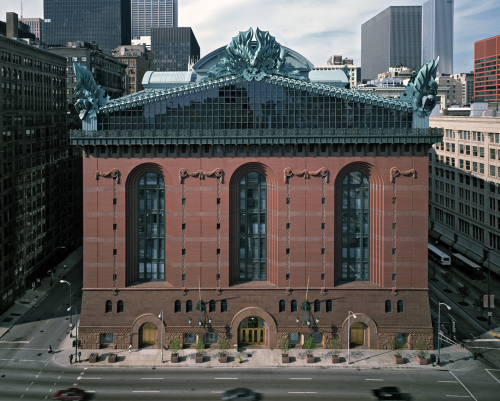

harold washington center in downtown chicago

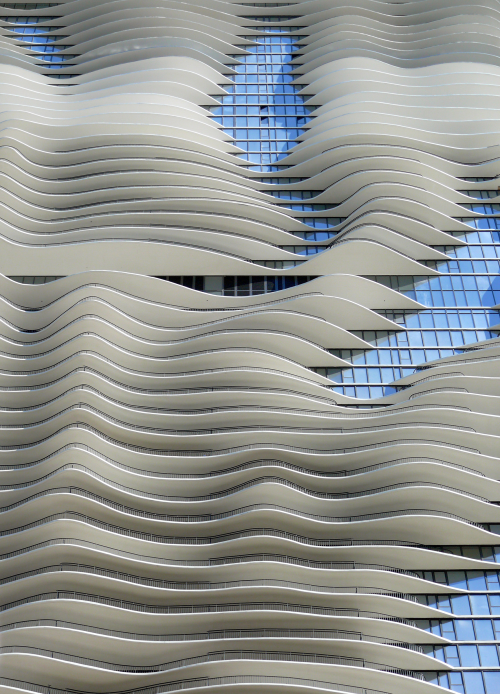

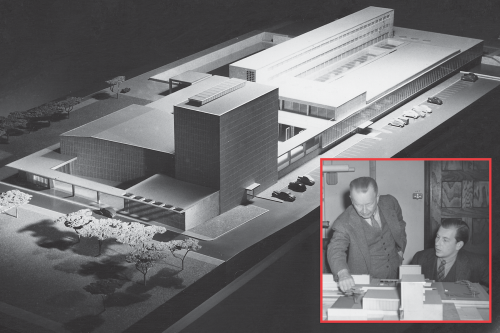

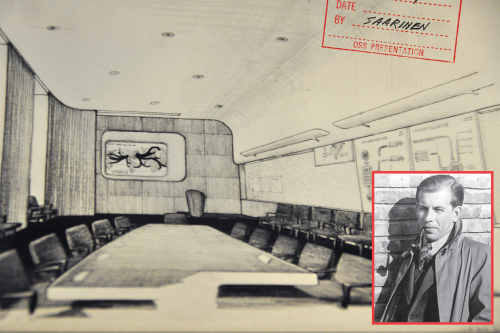

james a. baker III institute for public policy rice university houston texas