First porsche go-kart!

click > enlarge

click > enlarge

[ porsche ]

<a href=" about phil patton

about phil patton

click > enlarge

click > enlarge

[ porsche ]

<a href=" about phil patton

about phil patton

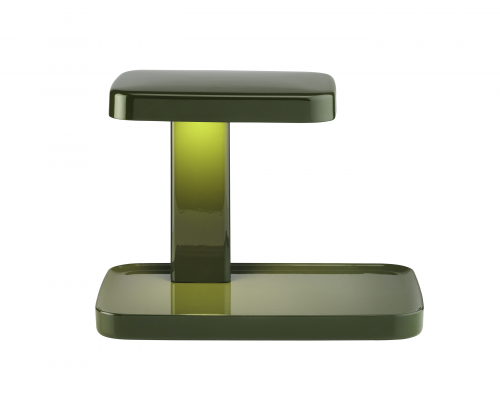

above> synapse

DesignApplause is talking to Argentinian designer Francisco Gomez Paz and US CEO of Luceplan, Giuseppe Butti, in the Miami Luminaire Design Lab Showroom. We’re all here for Design Miami 2012 and these men are here to introduce Francisco’s new light ‘Synapse’ to the US. It’s all part of Luminaire’s annual presentation of new production introductions during DesignMiami.

[DesignApplause] What brings the both of you here here?

[Francisco Gomez Paz] We’re here because Luminaire wishes to introduce a new product that I designed for Luceplan, the Synapse light. A system that works with LED light. It’s basically a divider of spaces. You can join it in different ways to create different configurations. Energy dividers for the space.

[DA] Is this a new product for 2012?

[FGP] We’re ready to put it on the market and we’re showing it here for the first time in America.

[DA] Francisco, tell us a little about you and where’s your design office located and what’s your office like?

[FGP] I’m Argentinian, born in Argentina. I studied in Argentina, but moved to Italy 14 years ago to study the Master in Design at Domus Academy. After a bit of working experience, I opened my office. Now I’m working with several companies.

[DA] The LED technology is causing quite a stir in the U.S. We’re starting to do away with the incandescent light bulb. In Europe, you have a bit of a head start on this.

[Giuseppe Butti] Yes. Europe banned the incandescent bulbs a year ago. The move is coming to the U.S. as well. The prime mover is the West coast with all their energy codes. The LED really started nudging out the halogen and incandescent bulb a few years ago with Title 20 or Title 24. This past year we saw a big trend toward the new light sources, like LEDs for commercial spaces, replacing florescent light sources. At residential levels, incandescent is still the most popular light source that people prefer.

[DA] People are hoarding incandescent light bulbs now.

[GB] I know. But the residential sector is starting to understand the LED a little bit better. The more it evolves toward a warmer light, away from the blue LED lights we used to see in the beginning, the more people are getting comfortable with adding new light sources in their homes.

[DA] I know the earlier LEDs were very unpredictable and unreliable. How long ago were you able to begin to invest in making quality lights?

[GB] I think that Luceplan, was one of the first companies to start experimenting in 2003-2004 with LED lights. We came out with the first LED product in 2006 called “Mix.” Since then, the entire industry has seen a big evolution. And our company now belongs to Philips which is one of the key producers of LED in the world. All our designers, like Francisco, take advantage of the R&D Development that we have. Every year we the LED technology allows us to do more than before. This is the big thing. It’s very important.

[Francisco Gomez Paz] In terms of design, I think it’s a big opportunity to try to find new languages. Then we can change all the earlier rules concerning sources of light. In my opinion, it’s a very nice opportunity to find new types of lights.

[DA] What are some of the differences from a design point of view that LED brings to you?

[FGP] There are huge differences. One is the light, the lamp, is a really tiny electronic element, not electric element, and is very small. 4×4 millimeters. It’s allowing us to put it in different types of situations that wasn’t possible before using the E27 lightbulb. It’s really amazing in terms of design. Luceplan encourages me to experiment to find new objects and new technology. Predictably there are many companies simply copying what was done before. That’s a big missed opportunity for many. Our decision is to try to imagine new frontiers of light.

[DA] How was the light conceived? Who approached who?

[FGP] This is an idea that came to me because one of the sources of inspiration a designer and an architect can have is to understand the human being. How you live and change. Of course, in the last 20 years, you have smaller houses and you remove walls because you need bigger spaces, for example it’s really common to mix the kitchen with the living room to share activities. But you still need in some cases sort of divider or filter. Hence the starting point for this idea. I tried to create a new way to divide spaces using light, LED light. I then simplified the idea using just one shape, a module, that could be configured in many interesting ways.

[DA] What are the materials used?

[FGP] Polycarbonate.

synapse

synapse

[DA] Looking at what you have on the wall, how many modules are up there?

[FGP] I know this may sound silly, I designed the assembly, but from here I can’t tell. I have to get closer to see a few seams then I can tell you.

[DA] How heavy is a module?

[FGP] They’re really light. We designed it wanting a lightweight solution and we used the minimum amount of plastic possible. Just two very light pieces of plastic that are welded together.

[DA] You had an idea. You go to Luceplan. Then you begin to collaborate with their engineers.

[FGP] Yes. I have a very good six-year relationship with Luceplan. We started with the Hope chandelier and we put to market in 2009 in Europe and 2010 here. It’s now a best seller at Luceplan and has allowed us to have a really good trusting relationship. I work almost in-house with the Luceplan engineers plus it spills over to my studio and workshop. Prototypes can be made at Luceplan or my office. A very open dialogue. That’s something really special of a relationship with Italian companies. That there’s such a close dialogue with a design company. A very open and free one.

[DA] We’re very fortunate having both the designer and the US CEO here. A business question: What percentage of your products are in the US and around the world?

[GB] The U.S. represents about 15% of total sales of Luceplan.

[DA] How long have you been in the U.S.?

[GB] Seven years in the US Before that I worked for 5 years for Luceplan in Milan as a sales and marketing director. We’ve been in the US since 1994, and it’s a long-term commitment. We are based in New York and New Jersey. We have a showroom in Soho. We have warehouses and corporate offices just outside of the city. However, the majority of the markets are the European markets. The most important markets are Germany, Italy, Scandinavia.

[DA] Luceplan is positioned as both contract and residential?

[GB] Yes, absolutely. The Luceplan line is for both markets. I would say that overall, we have about 65-70% is contract and the rest is residential. I must say that this percentage, which is quite unusual for Luceplan, is mainly due to the fact that the distribution of high-end lighting or high-end furniture stores in the US is not so wide. It’s not easy to find retail stores that can sell high-end products. This is a bit of a limit of the U.S. distribution. Certainly in the U.S. we are mainly contract oriented as far as retail.

[DA] Which are some of the U.S. cities you feel have a lot of potential?

[GB] The Northeast certainly. It’s one of our biggest markets. So is Miami. Mainly because there are a lot of South Americans and Europeans here that have bought apartments and houses and are almost residents here. The South American and European culture is very strong in Miami. The Northeast, Miami and then Canada. Southern California is another key market.

[DA] Francisco, do you just design lighting? It seems that there are so many architects doing products and vice versa.

[FGP] I do all kinds of products, not just lighting. My clients are mainly in Italy. I have a new client in America. As a designer, I’m very holistic in using different kinds of materials and means of creation for objects.

[DA] You’re strictly a product designer, not an architect? It seems in Europe there are many architects doing products and vice versa.

[FGP] I’m not an architect, even if I came from a family of them. Sometimes I’ll do some things for myself, but no I’m not. I think the same philosophies share something that is difficult to divide.

[DA] Where did you go to school?

[FGP] At the “Universidad Nacional de Cordoba” in Argentina, that is one of the oldest university of Argentina. After that I achieved a master at Domus Accademy in Milan.

[DA] What do you think of Design Miami?

[FGP] You have two different things going on in the city. The art show and the design show. The design show has matured and grown in importance attracting more people to talk about design.

[GB] Luceplan presented ‘Hope’ at Luminaire in 2010 and it was a big success. We’re presenting again tonight, introducing Synops to North America and hoping for the same kind of success.

hope

hope

[DA] Francisco, do you do limited edition pieces for the design galleries? or are you just concentrated on production?

[FGP] For now I concentrate just on production.

[DA] What does that mean ‘now?’

[FGP] My interest in the past was doing high production pieces because of the investment that went into the objects. There was more opportunity to experiment. Today’s technology is making it possible to experiment with small production with very good quality and that will encourage designers to participate because of the allure the freedom to experiment.

[DA] Tell us about your design principles? Do green and sustainable go into it?

[FGP] We can talk a long time about this. I don’t think you can put an eco label to design because I believe that it’s something that has always been in the philosophy of design. It’s impossible not think pollution and energy consumption. My philosophy is best described knowing the shape never starts in the beginning. I always try to start from a white paper free of preconceptions of ideas or shapes. For me, a shape is already an idea that is closed. My process is long, it involves philosophy, technology and the freedom to change the pre-existing. In the end of this process the shape almost magically appears.

[DA] Giuseppe, are you selling online?

[GB] We do online sales because in the US it’s very difficult not to do them. But it’s not the majority of our sales. The majority is the contract business or with architects on projects. Hospitality. Commercial. Residential. We have a network of retail stores like Luminaire and many others, but selective. Online is for us about 10% of our sales.

[DA] Do you have any stand-alone Luceplan retail stores in any city?

[GB] We have one in New York. In the heart of Soho. It’s our flagship store. So far this is the only one. It’s been open since 2007. Prior to that we had another showroom that was less a retail store, but more a showroom still in the Soho neighborhood on Houston Street and then we moved the our current location on Green Street.

giuseppe and francisco

giuseppe and francisco

[DA] How successful is it? Everyone I talk to in your business niche, the jury’s out for many. How is it working for you?

[GB] It’s good. It’s working. It’s still our number-one retail store in terms of sales. Certainly, with the New York costs, you have to see it as an overall advertising touchpoint for Luceplan worldwide. A lot of people from all over the world pass through Soho which is great for our brand image.

Another thing, our store in New York is more than a retail store, it’s also a showroom. We use that space to present to architects and designers. We organize events. For us, it works both ways. It’s yes on one side, a retail store so you can come in and buy a fixture. On the other side, it’s a moment that we use to present, in an ideal situation, a light fixture to an architect. You walk into stores where it’s difficult to figure out what that fixture can really give you. In our store, we pretend to say we have ideal vignettes and situations for our fixtures. We are happy with our store.

[DA] What’s Luceplan’s philosophy? Do you have an in-house design group?

[GB] Two of the founders are Paolo Rizzatto and Alberto Meda. They founded the company and are still designing for us. We also go to Francisco and many others from France, Italy, the US and all over the world. The important thing for us is that we receive a lot of proposals for new products and then it goes through a selection. If we think it is in line with the overall general philosophy, we are certainly open to new ideas and new products. We like to always been innovative not only with the materials, but also in the idea.

[DA] What is your background? Are you a businessman or are you a creative?

[GB] I’m strictly a business person. But I love design. I’ll let you alone with Francisco now.

[DA] Francisco, is there anything else you want to say that we have touched?

[FGP] I’d like to emphasize a really good relationship with Luceplan because we share many philosophies, and important ingredient. We like to do innovative things, but not just to do them. Design is an amazing tool to make a little progression to the world. Even in small pieces. Innovation always puts new value into our lives. That’s the role of design. You try to understand everything. Technology. Human beings. You try to do that little innovation step-by-step. That way we continue to innovate. This sharing of philosophy, the beautiful relationship we have with Luceplan…we’ve discussed many times where this world is going and how we can give to this world new objects that solve problems and that improve our lives in little steps.

apero

apero

[DA] Early-on in my interviews I used the label ‘design-driven’ objects. I felt compelled to use this label every time interviewing non-designers. A non-designer response almost always was ‘function-driven’ along with a well-thought out explanation.

[FGP] I would say idea-driven. An idea includes functions, materials and human beings. When philosophy is true to design, it transforms into something that is solid and original. What moves me are the ideas and then everything comes.

[DA] Your work is very clean. The architect Jon Ronan who’s work is also clean describes his work as ‘essential’ where he subtracts until he gets to the piece that is essential, that when you take that piece away the idea is broken. Can you describe your aesthetic?

[FGP] I cannot put myself in one aesthetic movement. Ideas can be expressed in completely different ways. There are things that are minimal and things that deserve more complexity.

I mean, it’s not something that I think of when I’m doing a project. If you see some of my designs, you will see lots of complexity but also at the same time, simplicity. My thinking is not so simple. Sometimes I love complexity. Nature is full of complexity. A tree is full of art and intelligence. I enjoy the intelligence of something and work with it. I don’t have any kind of preconception. If you take everything from a tree, what will you have? A tree is really complex. Even when it’s blooming, it’s full of flowers. Not just one. I love the freedom of nature, to be simple or complex. Depends on what you are trying to do.

[ francisco gomez paz ] [ luceplan ] [ luminaire ]

1/4> synapse | fgp | 2011

5/11> hope | fgp | | luceplan | 2010

12> nothing | fgp | luceplan | 2012

13> comodoro | fgp | danese | 2008

14> solar bottle | alberto meda and fgp | 2007

15> omero | fgp | driade |2006

16> ovidio | fgp | danese | 2005

17/18> apero | fgp | sumampa | 2004

19> otto watt | alberto meda | luceplan | 2011

20> petale | odile dec1 | luceplan | 2011

21> honeycomb | | habits studio | luceplan |2011

22> archetype | good morning technologies | luceplan | 2010

23> any | habits studio | luceplan | 2010

click > enlarge

click > enlarge

DesignApplause met Leo and Angie Fajardo at an after party at Housewares Show 2013. They had something to show and they didn’t have a booth. After chatting with them for 15 minutes and seeing what they were up to DA joined their team of supporters. Kickstarter has a full-blown presentation [ check it out ]

[ trinkits design ]

click > enlarge

click > enlarge

Discover Design is in it’s 3rd year. Over 100 hand-picked suppliers contributed to this year’s show in which 200 products were juried. The juried finalists are on display at a Discover Design exhibition booth. There are two categories, product design and collections. There are two winners in each of those categories, Global Honoree and Finalist as seen below.

product design global honoree

c-pump | unique soap pump that can be operated with the back of one hand

[ joseph joseph ]

product design global honoree

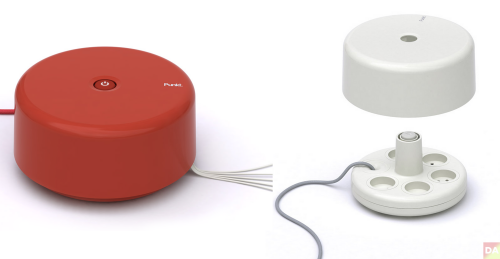

ES.01 extension socket | cleans up clutter | designer george moanack under art direction of jasper morrison.

[ george moanack ] [ jasper morrison ] [ punkt ]

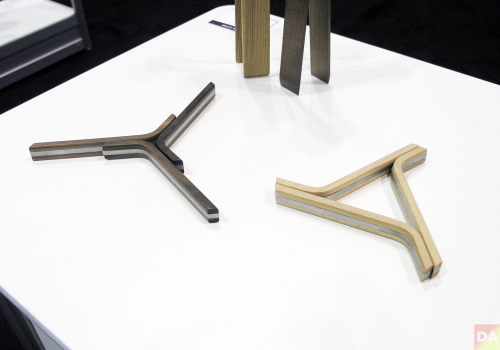

product design global honoree

troika trivet | an adjustable, easily stored adaptive serving tool designed by cutter hutton

[ cutter hutton ] [ teroforma ]

best collection design global honoree

mu | cutlery collection | distinct hexagonal handle which took two years to produce due to difficult production process | designed by japanese architect toyo ito

[ alessi ] [ toyo ito ]

[ product design finalists ]

sencha tea maker | simple. brew and serve tea without removing the strainer | [ blomus ]

green farm | grow sprouts and herbs indoors in terracotta trays | [ cult design ]

mini supoon | dirty head sits off of counter and also measures a perfect tsp/tblsp | [ dreamfarm ]

couleur | clever nesting of teapot cup and saucer | [ kinto ]

turner spoon | world’s only turner that you can also use as a spoon | [ magisso ]

cool breather | aerates bottle of white wine in two minutes and keeps wine cool |[ menu ]

big happy family | vertical garden / organizational system. plates of powder coated steel and vessels from polypropylene with neodymium magnets | [ urbio ]

click > enlarge

click > enlarge

Few designers manage to navigate with such conviction between design, art and craft, between social conscience and mass market, between sustainability and aesthetic value. Stephen Burks has a unique voice.

above> Dala | Dedon | 2012 | Inspired by improvised seating in the developing world, Dala is Stephen’s first collaboration with woven outdoor furniture manufacturer Dedon. Dala means “to make” in Senegalese and “to take” in Tagalog, the language of the Philippines, where Stephen spent over a week collaborating with artisans there to perfect the collection. In addition to the innovative use of an expanded aluminum structure, each Dala is woven with a 75 percent recycled polyethylene and Tetra-Pak extruded Dedon fiber.

Play | Kvadrat Hallingdal 65 Commission | 2012 | 7 Renowned Curators, 32 Talented Designers, 1 Iconic Textile. Selected by US curator Jeffrey Bernett and exhibited at the Jil Sander showroom during the 2012 Salone del Mobile as part of Kvadrat’s Hallingdal 65 anniversary exhibition, Stephen’s project was quite simply a textile display system called Play. Play is free-standing. Play is human scale. Play is portable. Play is effortless. Play hides things. Play absorbs sound. Play defines space. Play is colorful.

above> Panier Collection | Chevalier Edition | 2012 | Inspired by the spiral pattern of hand woven baskets, the Panier carpets for Parisian brand Chevalier Edition, are organic islands of hand-knotted color for the home.

above> Roping | Dedar | After perusing the beautifully delicate and graphically arresting collection of Dedar Milano, in collaboration with Dedar creative director, Raffaele Fabrizio, Stephen came to the conclusion that what all textiles have in common is “A Thread!” or many threads in composition with each other. Using the thread as a fundamental element or starting point for the exploration of Dedar Roping, Stephen quickly began looking for a more structurally analogous material from which to construct something 3-dimensional. For Dedar Roping, Stephen would explore ropes ability to become supportive in section, exposing all of its many loose threads in relation to the sophisticated variety of trimmings offered by Dedar Milano.

above/below> inside out | swarovski crystal lighting collection | 2011 | Chandeliers and sconces using crystals in a functional rather than a decorative manner. The basic primary shapes are lit from the inside with LEDs creating a prismatic effect of refracted light.

[ ready made projects ] click > enlarge

click > enlarge

Alessi’s Spring/Summer 2013 collection again brings out the animal(s) within us. And a great deal of art and form assert without loss of function.

Jasper Morrison presents ‘Mame’ a minimalistic press-filter coffee maker. Coffee bean icon personalizes the piece.

The super star in Spring/Summer 2013 may very well be the kitschy ‘Duck Timer’ designed by Eero Aarnio. When it’s time to turn off the heat the duck quacks.

There’s quite a bit of kitchen objects including cookware, cutlery, china, oil-vinegar cruets and the duck timer among other items.

Last year’s Fall Winter 2012 collection introduced ‘Dressed” by Marcel Wonders, an effort to reposition perceived low-end aluminum cookware: Mission accomplished. In 2013 the designer introduces 18/10 stainless steel with magnetic bases to the family of cookware. Applying an exclusive deep-cut pattern to the handles and covers provides what’s needed to transition from kitchen to table.

Yet another animal is ‘Kastor’ a shiny beaver which gnaws pencils. The sharpener also functions as a paperweight.

PZ06 and PZ07. Pepper and spice caster. Peter Zumthor designer.

3> Duck Timer. Designer Eero Aarnio

4> Mame. Jasper Morrison

5> Acquerello. Colorful decoration added to last year’s bone white china. Guido Venturini

6> Dressed. Marcel Wanders

7> PCHO5/24. A set of 18/10 stainless steel fruit holders. Pierre Charpin

8> Joy n.1. A 18/10 stainless centerpiece. Claudia Raimondo

9> Tower. 5-set measuring devices inspired by balance weights. Monica Förster

10> ecco!. Fruit holder in 18/10 stainless or colored epoxy resin. Massimo Mariani

11> MU. Cutlery set. Unique hexagonal handle section “MU in Japanese. Toyo Ito

12> youSpoon. Your own personal accessory teaspoon. Marta Sansoni and LPWK

13> Kastor. Rodrigo Torres

14> CrissCross. Anodized aluminum multi-purpose basket. Eero Aarnio

15> Pick-Up. A new Alessi typology, a side-table magazine stand. Jakob Wagner

16> Mantel clock. A new edition (1988) maple-veneered clock. Michael Graves

17> PZ04 > 08. Complete set of oil.vinegar cruets, castors. Glass and 18/10. Peter Zumthor

18> A Lotus Leaf. Centerpiece in new steel colored epoxy resin added to 2012 edition. Chang Yung Ho

[ alessi ]

click > enlarge

click > enlarge

VIPP, is known for its covered pedal bins, a product marginally improved since the first one made in 1939. Today they also make kitchen and bathroom accessories. The ‘table’ is their first foray into furniture. The Vipp table features a table top made of untreated, recycled teak planks, making each table unique. Every table top thus stands out with its own distinctive character.

The table frame is constructed in powder coated aluminum and is assembled with solid corner profiles, a steel wire stabilizer and countersunk screws, giving the table an industrial feel. The table is equipped with set screws making it possible to adapt to uneven floors.

“Now that we have a whole Vipp kitchen concept, it seemed very natural to extend the collection with a table to complete the look. The table frame is the same used for the kitchen modules, ensuring stability and visual coherence. For the table top we chose natural wood that can stand daily wear and tear – it will actually develop a beautiful patina over time and create contrast to the smooth aluminum”, Morten Bo Jensen, Vipp Chief Designer. The table is available with a frame in matte black or gloss white, and is sold in the Vipp flagship store in Copenhagen. [ VIPP ]

Alma, a collection of many interchangeable parts, including a birch table, an ash chair, felt, steel rods, and wing nuts. The collection needs only a dining table and shelves to completely furnish your space. Alma represents two months of work from the recent graduate in order to participate in Feria Habitat Valencia 2012 > Nude he was invited to.

above> csys desk light

[DesignApplause] This interview took place during Neocon 2012 and we’re at the James Hotel with Jake Dyson. Jake, please tell us a little bit of your background and what you’re working environment is like?

[Jake Dyson] I studied product design at St. John Martin’s in London. The course was very aesthetic-based, all about styling. I actually made a water power generator that you attach to drain pipes in buildings so when it rains or you empty the toilet, it generates electricity and puts the heat back into the water system. The College thought this was a bit out of place, but it’s what I was interested in — moving mechanics.

I just did what I wanted to do and really enjoyed it. I patented that product. When I moved on from college to make money I found myself in interior design. But I wasn’t designing the colors of the wall or putting carpets in a space. I was making gadget-sensor-activated furniture, cabinets that opened by aesthetic or sensor tacks. It was quite interesting to work in this environment and it fired up my interest in product mechanics.

To be honest, I found designing for interiors quite boring because the tolerances are so great. You can have 5 millimeters gap here and there and it’s not critical. For product design and mechanisms it comes down to one-thousands of millimeter tolerances and that precision is much more challenging and exciting.

My next job was with product design office, Cock & Hen, Henry Slack and David Cock. One of their clients, David Linley Furniture, produced various products that required a fire blowing process and taught me about blow molding. One project was to make a blow-molded watering can with a watering butt and the tooling was very complex. It was that environment that I became interested in manufacturing and the processes evolved.

What I wasn’t learning was how you take a concept to the shop floor to manufacture and then sell it. So I took a backwards step and went to work for my father, which in my opinion, was one of the greatest training grounds for a design engineer.

[DA] What do you mean by backwards step?

[JD] It was important for me and my self-esteem to carve my own path in life. But if I really wanted to do that, I had to learn how. I felt the need to carve a self-made path on one end and at the other end was learn the extremely difficult path towards being a product designer.

[DA] Benjamin Franklin, a U.S. president and an inventor made famous by flying a kite in a lightning storm said, ‘Experience is the best of schools but only fools attend.

[JD] There’s definitely a fool in me. At Dyson I worked for 2 years with a team of designers and engineers taking a conceptual idea right through to the point of manufacture. I learned the process of experimentation, testing, getting things working correctly. That period also included computer-generated design and processes of manufacture. Although I can’t say I knew everything, it gave me a good feeling that I could go and do this on my own.

It was at that point that I moved back to London and found a very small garage in Wandsworth and started experimenting with a ceiling fan idea I had. It was a very mechanical clever ceiling fan that rotated around on the ceiling with its own reaction. There were two blades like a helicopter with one working the opposite direction of the other and it was bolt driven.

It was a strange fiscal phenomenon where one blade was fighting against the air against the other blade. The reaction of the main drive blade drove the system around the ceiling in a very controlled manner. I had created something I really didn’t really understand the physics of why it was moving in a controlled way. I got together with Professor John Whitehurst who happened to be the pioneer of the first-ever electronic washing machine. He was working for Bosch at the time and decided to come and work with me for 6 months.

We had to lean over this fan with blades going at 700 rpm, very close to our necks mind you, trying to understand the physics of the strange oscillations the fan produced. Whitehurst also designed a lawn mower, Flymote, which has a similar principle. When you cut the grass, the mower wants to go in one direction as it hovers. Both the fan and mower are extremely difficult to manufacture because of safety reasons and the level of testing and engineering required to take it to that level. I licensed that product and with that money, I set up my own studio in London.

jake with the motorlight

jake with the motorlight

I also started working on a lighting idea from my interior design days exploring the limitations of lighting. People were up-lighting spot or flood bulbs and hiding them behind sofas or plant holders and they only could use either one or the other bulb. And it wasn’t a lighting piece people wanted to see in the roof. They were limited by the throw of light being either a narrow or a wide beam with no flexibility in between. I thought it would be fantastic to make a lamp which gave the function of all these degrees and angles of light, while also creating a beautiful piece you’d want to see in the room. I spent 2 years developing a focusing mechanism and the drive system. The Motorlight Floor launched in 2006 and it’s still on the market and in Europe, and Hong Kong.

Another lighting idea was to have an angle-adjustable wall light and I thought wouldn’t it be great if it was remote-controlled. These lights could be controlled and synchronized to create light sculptures on the wall and theatrical mood lighting as well. Again, another 2 years developing the product. That Motorlight Wall is also selling in those places.

The interesting thing about the second product is the use of main voltage halogen, which at that time was being targeted to be out-phased in countries because of the carbon footprint. Many commercial products were already turning their back on that technology. But during the development of Motorlight Wall LEDs weren’t right for the market. Just as I launched Motorlight Wall LED’s took off. I was caught between timing in the marketplace and transitional technologies.

[DA] What time period are we talking about? At this point in time the U.K. is controlling the kind of bulbs one can buy. When did the LED hit the marketplace in the U.K.?

[JD] LEDs have been around for 8-10 years in lighting products. They were initially invented in the 1960s in the U.S.

[DA] LEDs in the U.S. were limited to electronics indicator lights, holiday lights, most recently flashlights and automobile tail and running lamps.

[JD] Despite the limited applications people were pitching the technology to make them bright enough to be used for ambient and task lighting. A good 10 years of pitching.

It took a bit to truly understand an underlying problem. The problem was a loosely standardized chip manufacturing industry making it all but impossible to select consistent and specific colors of lights. When office buildings would buy a ceiling lighting system for example, the light color would be different on each unit. Also at this time the Chinese flooded the market with commercial lights encased largely in plastic with colors that might fade from pink to green. With all the poor offerings, it’s understandable how the folks were put off with the LED.

In the last five years or so the chips have improved and are more consistent and reliable. That’s why the huge boom in the LED lighting industry. But while that boom is great for the environment there’s a bit of a downside in the sense that in the race to compete in the marketplace too many of the LEDs were produced too quickly.

A bit like the fashion world with seasonal collections. There was not enough attention given to the science and technology behind how to make the product reliable and endurable which is important to the quality of light. It was more about quickly getting to market to sell at a right price or to make beautiful products people wanted to buy.

During this five-year period while working on one of my products, we decided to convert to LED. I’ve learned early on that you are unwise to skip an element of experimentation, a period that you have to do to discover the problem yourself before taking the product to market. You’re also wise to seek the advice of experts in the field so I flew to Malaysia to meet the head of Osram in Asia. I went to their new wafer plantation factory in Panang, where they developed the ability to produce a hundred million LEDs a week.

[DA] Why this particular company?

[JD] I recognized that Osram was creating very nice, warm white LEDs, a color temperature where demand outweighed supply. Interestingly, everyone was using white and blue LEDs because they wanted to falsify the brightness of the chip. The misconception, the whiter the light the greater the perception that the light gives off a lot of light

[DA] Is the warmer LED a redder light, the color temperature of the incandescent?

[JD] Yes, that’s the aim. As you know, in the UK the incandescent was taken away and there was the threat that halogen would be too. And the industry was getting concerned because the incandescent was the most desired color. Everyone was upset.

[DA] Is the desire for warm light mostly for residential? I would think a cool neutral light is more of a commercial temperature.

[JD] Well there’s a debate on this one. The cold daylight light was introduced to the office.

[DA] So daylight light is cold?

[JD] Well, artificial daylight is cold. Real daylight is not cold because the sun is yellow. Of interest, yellow is probably the first color you see when you wake up when you’re born. Daylight is also mixed with so many other colors, reflections from surfaces and objects around you. It’s not realistic for one artificial light source to replicate daylight accurately.

Did you know offices were using artificial daylight to keep workers awake later in the day, which isn’t natural. It’s ok in the morning, but later in the day you don’t want to be woken up. It’s not a comfortable working condition and there are better ways of doing it.

At this time the compact florescent technology was pushed by energy companies and governments to replace the incandescent light bulbs. In many cases, it was more about big energy companies wanting to increase their profits in a disposable environment. There is an argument that says the energy required to make compact florescent light has a large carbon footprint than making the incandescent. The fact that energy-saving light bulbs last for 10,000 hours is rubbish as well. It’s actually 2,000. There was a survey conducted in Germany where 70% of compressed florescent bulbs failed after 2,000 hours and reduced the level of light by half after 1,000.

Another matter is how uninformed and uneducated the public is regarding compact florescence. In the event of breaking one in your home, it’s advisable to put on protected eyewear, masks, open all your windows and evacuate your children and pets because there’s mercury inside the florescent.

Most of instructions however are directed at disposing compact florescence in commercial but not residential settings. There was an awful scheme by an energy company in England three years ago where they put four brochures in every letterbox in every house in England as a promotional stunt to avoid paying taxes. The government felt this was an incentive for manufactures to produce greener products and condoned the ploy.

[DA] So the government subsidized this?

[JD] No not directly and there was no government control policy and the energy companies made their own rules. Many compact fluorescents were made. Every household received four lights in their letterbox. Those who tried one and the first try didn’t give any light, most threw the other three in the bin. You can imagine four light bulbs for every house getting trashed and not enough knew the bulbs contained mercury. Obviously, a more informed public would have behaved quite differently.

[DA] Let’s get back to the quality of light. A better understanding of what you feel is good or poor light.

[JD] We can start with the shortcomings of the light bulb and what we have become accustomed to. We know that familiarity breeds comfort and that goes for lighting. The color in the lightbulb, which we feel is the desired color is pretty awful. The warm white is too orange and pink and makes everything overly red. At the other end cool white is too white and makes people tense, in some cases literally migraine-creating.

Not to mention the bulb is very bulky. The light fittings that have to accomodate the bulb are huge. The light emanating from the bulb requires reflectors to contain the light and throw it downwards. The net effect is bouncing light around objects to channel it. Whereas LEDs are very directional without much loss of light.

[DA] I’ve just become aware of the size of the bulb and the fixtures relative to the LED. Somewhat like comparing the 80s brick-size mobile phone with todays offerings.

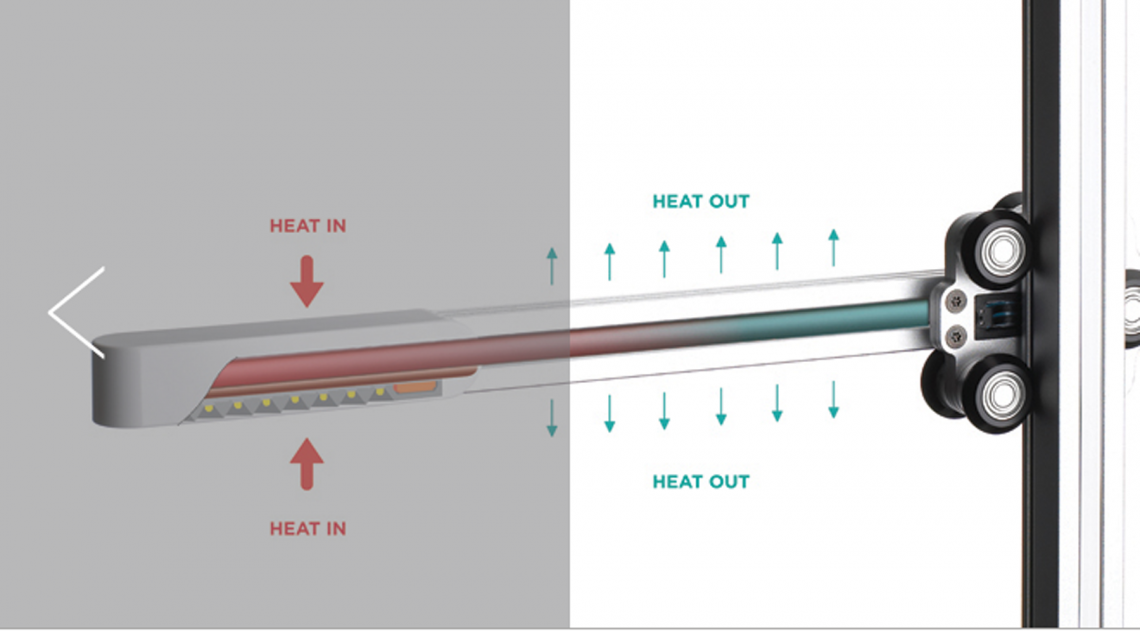

[JD] Oh, much, much worse. All these happenings prompted looking back to move forward. My experimentation with LEDs and working with the head of R&D for OZRAM??, prompted the question, ‘How can you make an LED product last for life?’ His response was that you have to run the LEDs very, very cool. In fact, the optimum temperature for running an LED is -200 Centigrade. At that temperature, the LED can be powered with its maximum brightness for infinity.

You can’t make desk lamps with refrigeration units. You would need compressors and gas. We did spend a lot of time on very complex designs to get the LEDs to run as cool as possible in our wall light. That’s how we learned LEDs are semi-conductors, an element used in computers. We bought loads of laptops from Ebay and ripped them to pieces to see how they were utilizing a semi-conductor. We learned the computer uses heat pipes to channel the heat away from the heat source and send it to the cooling fan. Fans are required in an enclosed environment, the computer body.

The LED lights that are not thermally managed properly start to change color. The reason, the LED in a light is actually a blue LED with phosphor on top of it and dyed to make the light white. If the LED is run too hot, the phosphor cracks up and the blue light filters through, mixing with the yellow of the phosphor. The light can also get a bit green and in some cases, a bit pinkish. In a commercial environment twenty ceiling lights can all be different colors after one year.

[DA] What is a heat pipe? A highly conductive metal?

[JD] No. Heat pipes were originally used in satellites. A satellite is -200C on the shade side and +200C on the sun side. Instruments inside of the satellite require a controlled temperature and it’s done by channeling all the heat from one side across the cold on the other side to reach a desired temperature. The heat pipe is a tube in a vacuum. You put a drop of moisture in water and evacuate the air, like in outer-space. The water in a vacuum boils at a very low temperature and vaporizes and shoots to the cooler end of the pipe. At the cool end, the vapor condenses back into moisture and by capillary action runs all the way down the tube to the hot end again. You have a cycle of vapor shooting via the center and moisture coming down the walls. That’s the basic principle of a heat pipe. It’s not new technology. It’s been around since the 60s, but it’s been refined and improved and literally under our noses in computers and servers. Its reliability has been proven. You’re more likely to see a failure in electronics than the heat pipe.

We took a box of cooling units and heat pipes to CCI Technologies in Malaysia. Amazingly, the parts in our box, they said they made every single one of them. I learned they were the biggest microprocessor cooling manufacturing company in the world and made units for Apple, Samsung, Hewlett-Packard and Intel and made 7 million units a month. They invited me to go to Taiwan to see one of their factories. It was a no-brainer to work with this company to develop a heat pipe cooling assembly for an LED light.

We designed my desk light together. It’s how we achieved an incredibly efficient cooling system. The light has been redesigned and now functions on the longest six millimeter heat pipe that’s taken to market. This breakthrough technology is designed specifically for me. It’s a great example of how you work with an expert to make something effective and reliable. The alternative is to throw in a heat pipe into a product without understanding how to use it.

above> jake with csys

[DA] Your light is more than just a pretty thing.

[JD] Absolutely. We don’t start with a sketch for a pretty object. We start from the reverse end. We experiment with chemistry sets and engineering. I built my own climate chamber room to simulate the effects of no air convection and to take heat readings in insulated chambers. We also ripped apart a few serious industry leader’s lights. Ripped them to pieces to see how effective their heat system is. We realized few were doing anything really refined. The common practice is overcompensating with masses of aluminium on the back of the LED chips. The aluminium gets hot cooking the chip. Most want to get the next product out. Our light took two years to design and test, making sure it’s reliable as well.

[DA] Can you say at this point that your light is unique?

[JD] Yes. I would say there are one or two other heat pipes used in LED lighting. I can say that our product uses the technology correctly, based on 25 years of computer experience.

[DA] Jake, is it ok to say it reminds me of designing a revolutionary vacuum cleaner?

[JD] If you’re trying to do something no one’s done before, you’re out in the wind. You could go in any direction. It’s not easy making new technology reliable and proving that it works. That’s what takes months and months and months. My father and their company, the technology being cyclone technology, are always working to make the products smaller and more efficient. This process involves a great deal of experimentation.

To give an example, we did try to make our own heat pipes with a product that sucks out air from a wine bottle to keep the wine fresh. But you know, it’s trial and error. And the product aesthetic detailing is last. Our desk light, for example, there isn’t one surface piece of material that doesn’t have a critical role. It’s completely refined and in my opinion, very, very sexy because being honest and showing the workings of something can be intriguing and very, very exciting. When you’re using a product and it’s performing well, it’s always going to be a satisfying experience.

[DA] How long do your products last?

[JD] We have a five-year manufacturer’s warrantee on a product. I really wanted to guarantee the LEDs for 37 years. But what happens if our plug unit fails and our customer on the other side of the world says the LEDs don’t work anymore. I can’t determine whether it’s the plug that failed or something else. I’d like to say, and you can take my verbal reassurance, that the LEDs will last that long.

[DA] The new LEDs coming out for consumer use to replace the incandescent carry guarantees of 18-25 years. The LEDs are at the mercy of the hardware. Are they just taking a deep breath in order to quickly grow a market?

[JD] Here are two thoughts. One is the 18-25 years are benchmarked on seven hours of use a day. My quotation of 37 years is based on 12 hours use a day.

Two, manufacturers who supply the LED chips may state a chip life of 50,000 hours. They know their chips are going into products that are running way too hot. The truth, an LED can have 220,000 hour life or longer if you run cooler. But they say 50,000 hours.

Right now lighting specifications are very misleading because everyone is measuring their products by a different standard. Someone can tell you that a compact florescent has the same light output as a 50-watt halogen or that an LED replacement spotlight has the same light output as a 50-watt halogen though you can barely read with the LED spot. The reason is the light level is measured in the beam of light, not in the overall light given off in the room. They’re allowed to make these claims under current non-standards.

[DA] You mention the different light temperatures that occur during the day. One color when you wake up, another by the time your are ready for bed. Is there merit to a bulb that is one color in the morning and changes color and makes you more relaxed at night?

[JD] Probably but at the same time, it’s very subjective. Everyone wants different things with light. I mean it’s like genetically modified food. I don’t know how much we should tease our eyes but I did see something very, very interesting. I don’t remember the source but it was a fish tank. A company was tuning LEDs to allow the algae and plants in the fish tank to stay alive but never grow. So you don’t have to clean it or cut the weeds.

[DA] Possible?

[JD] It’s possible, I think. It is interesting. You notice how greenhouses are being switched over to LEDs and I bet it’s not just about energy use.

[DA] Genetically modified food through light.

[JD] The produce that has been grown under sodium lights may just be different than produce under LEDs. I’m not going to make an adjustable light which one week puts me in Hawaii and another in London. But it’d be interesting to see the reaction if another company gave it a go.

[DA] I was supposed to interview Ross Lovegrove in Milan, but it didn’t go through. But I did a bit of research on the both of to you. Do you talk to him?

[JD] We’ve never had the opportunity to chat. I’ve met Ingo Mauer several times. We’re two very different types of designers.

[DA] Any other lights you can talk about it?

[JD] We’ve launched a much larger version of the desk light for the floor so it’ll tower over sofas and chairs, but has the same technology, movement and articulation. Just a bigger, more wonderful light.

You know, there’s legislation now coming to place. Quite a few office buildings are taking out overhead lighting because of its servicing and energy consumption. It’s headed towards more localized lighting. What a fantastic time to be doing task lights! Good timing for a change.

[DA] I was talking to an ergonomist and his company was building furniture and task environments in such a way that it improves the well-being of work over a long period of time. It seems obvious that the lighting plays an equally important part.

[JD] Yes of course and maybe someone should be developing a mindset for a longer living light source. I’ve concentrated on making an LED product last for life. Everyone should approach light design that way. We’re now seeing disposable LED light bulbs based on the assumption that commercial premises have a refit every 7 years despite that specifiers are willing to accept 30,000-50,000 hours life on a LED downlight fitting. A well-designed interior, including light, should have a long shelf life.

That’s the whole point of sustainable architecture. And I was being slightly rude about the Hawaii/London lighting. The color of light is absolutely important. It may be my hatred for compact florescence and white light that has driven me towards a product with very nice warm white light. And the realization the marketplace is not worried about losing the light bulb but losing the color of light that comes out of it. And the realization that some bought beautiful lights in the 70s or 80s and don’t want to stick compact florescence that looks like there’s a Mr. Whippy Ice Cream coming out of the front of it.

[DA] You’re achieving a bit of sustainability just by the longevity of your light. That’s a statement. Make sure you have a date stamped on your light.

[JD] Actually, that’s a very good idea. There is a serial number on the side. There is a lot of movement at the moment where people are using the volume of recyclable material in their product as a marketing point. I’ve seen one or two products that are almost entirely CNC aluminium, a key marketing point that their product can be recycled. We have lot of completely refined aluminum extrusions. We could recycle it. But there’s a very small quantity of plastic which is absolutely essential. You have to have plastic in things. There we go.

[DA] Jake, is there anything you want to say that we didn’t talk about?

[JD] Maybe restate that there’s one other similarity with Dyson and that is that we design a product, engineer it, test it, market it, manufacture it, and sell it all ourselves. We’re not a business that designs conceptually and hands it over to another company to produce. We do everything ourselves. We oversee a company in Malaysia and all of the supply chain. The quality of how things are made. Within a small design company, that’s quite unique I think. This model is critical as it’s the only possible way to maintain pure quality control.

On 15 December the 2012 Good Design Award winners were announced. Thousands of entries were vetted to highlight the best designs based on innovation, form, materials, construction, concept, function, utility and aesthetic appeal. Select 2012 winners on this page via [ BDE ] The [ complete list ] of winners.

Lento Lounge Chair | Harry Koskinen | Friends of Industry | Artek | 2006-11

![]()

Pixel Graphic | Heather Bush, Carnegie Design Studio | Carnegie Fabric | 2010-11

Piani Lamps | Ronan & Erwan Bouroullec | Flos | 2011

minuscule Chair and Table | Cecilie Manz | Fritz Hansen | 2012

ZŌN® Max Air Purifier | Stefan Spoerl and Andrzej Loreth | Humanscale | 2011-12

Nadal Throw | Rosita Missoni | MissoniHome | 2012

Dibujo tinta | Eduardo Chillada | Nanimarquina | 1957

1> AlessiLux |Giovanni Alessi Anghini and Gabriele Chiave | GAA Design Farm | Alessi | 2010-11

2> Floating Earth Tray | Ma Yansong, MAD Architects | Alessi SpA | 2011-11

3> Ape Aperitivo | Giulio Liacchetti Industrial Design | Alessi | 2011-12

4> Ming Tray | Zhang Standardarchitecture | Alessi | 2010-11

5> Lento Lounge Chair | Harry Koskinen | Friends of Industry | Artek | 2006-11

6> Pixel Graphic | Heather Bush, Carnegie Design Studio | Carnegie Fabric | 2010-11

7> Piani Lamps | Ronan & Erwan Bouroullec | Flos | 2011

8> D’E-light | Philippe Starck, Starck Network | Flos | 2011

9> APPS Luminaire | Jorge Herrera, | Flos | 2011- 12

10> minuscule Chair and Table | Cecilie Manz | Fritz Hansen | 2012

11> Float Sit -Stand Height-Adjustable Table | Humanscale Design Studio | Humanscale | 2012

12> ZŌN® Max Air Purifier | Stefan Spoerl and Andrzej Loreth | Humanscale | 2011-12

13> Nadal Throw | Rosita Missoni | MissoniHome | 2012

14> Dibujo tinta | Eduardo Chillada | Nanimarquina | 1957

15> Manos | Eduardo Chillada | Nanimarquina | 1995

[ good design award ] is the oldest Design Awards program organized annually by The Chicago Athenaeum Museum of Architecture and Design in cooperation with the European Centre for Architecture, Art, Design and Urban Studies. The awards program covers new consumer products designed and manufactured in Europe, Asia, Africa, and North and South America. The trademarked awards were created in Chicago in 1950 by three architects: Eero Saarinen, Charles and Ray Eames and Edgar Kaufmann, Jr. The logo was designed the same year by the late Chicago graphic designer, Mort Goldsholl.

All content ©2007 > 2024 DesignApplause