this post was originally written on 10 november 2009 / we’ve updated the photo gallery

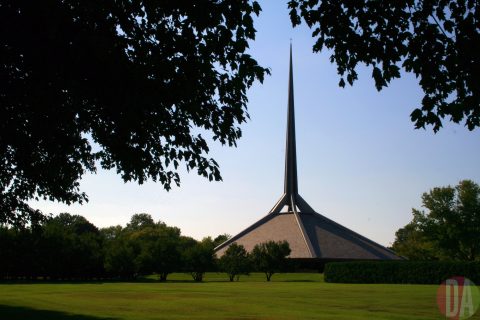

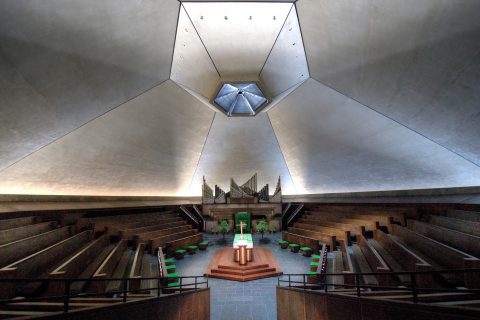

today, except for a few projects like the moribund twa terminal at jfk, eero saarinen is better known for his furniture than his buildings.

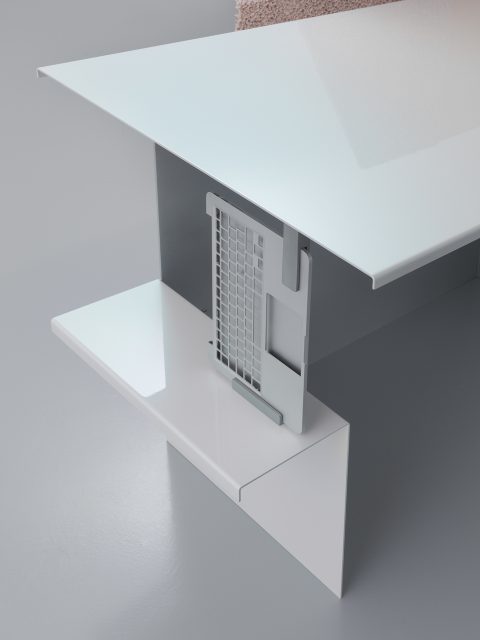

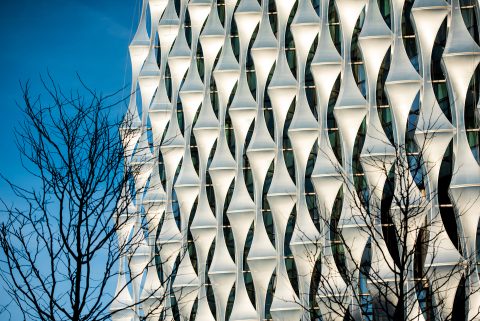

his “womb” chairs and pedestal tables (designed, he said, to “clear up the slum of legs” in the american home) are still big sellers for knoll. but does anyone remember that he designed the beautifully soaring dulles airport? or cbs’s “black rock” headquarters? saarinen might find it oddly familiar that his chairs have eclipsed his architectural achievements: early in his career, he’d struggled against the long shadow cast by his father, eliel, the revered finnish architect who’d founded their bloomfield hills firm, just outside detroit.

two years before eliel’s death in 1950, eero had rushed to pop a champagne cork and toast his papa after a telegram arrived congratulating saarinen on his winning design for a memorial to commemorate the louisiana purchase in st. louis. but the cable was a mistake: eero had submitted his own idea—he was the winner, not his father.

his scheme for the epic steel arch in st. louis was a prelude to his future designs for corporate offices, embassies, and airports, veering away from his father’s sensibility and embodying instead the triumphal spirit and swaggering power of postwar america. saarinen gets his due in a fascinating exhibit at the museum of the city of new york, “eero saarinen: shaping the future,” that explores his impact on the 1950s and ’60s. what you don’t expect is to discover the impact of a woman whom saarinen himself has come to overshadow, though she was a cultural force in her own right. the woman was his wife.

aline louchheim, an art critic for the new york times, understood how eero had wrestled with his father’s ghost. she arrived in michigan on a wintry day in 1953 to write a story on saarinen the son. after two days of interviews and a tour of the construction of his latest project—a massive and innovative 25-building complex for general motors—she declared in her article that the architect, then 42, had freed himself from his father to follow his own direction. his designs, she wrote, were giving imaginative form to contemporary industrial civilization and becoming “an expression of our way of life.”

but there was a secret behind those glowing words, one that, surprisingly, didn’t prevent her from writing them: aline and eero had had an instant attraction. she was an accomplished, socially connected, attractive blonde divorcée; after she’d flown back to new york, he wrote her polite letters, typed by his secretary—as well as handwritten love notes that his secretary surely never saw. the next year, after eero divorced his wife, the couple married, and she continued to promote his work to a wide circle of media friends. at one point, she even confessed in a letter to her mentor bernard berenson, the art connoisseur, “now i observe myself ardently promulgating the eero-myth.” not that she didn’t believe passionately in her husband’s talent—she did.

what’s surprising is that she didn’t sublimate her own ego or her work for her husband’s career. instead, she exemplified a select species of ambitious, intellectual american women who managed to thrive in the 1940s and ’50s, while most of their sex were carpooling the kids in the new postwar suburbs. aline not only continued to work as a journalist during her marriage to saarinen, she also won a guggenheim fellowship and published a book about art collectors, the proud possessors, that became a bestseller. after saarinen’s untimely death, she reinvented herself as a television news correspondent and became the first woman network bureau chief when nbc sent her to paris. if his optimistic designs for gm, ibm, and twa seemed rooted in the historical moment of eisenhower’s america, so, too, did her achievements. in the pre–betty friedan era, aline succeeded by using all the tools at her disposal—including her femininity and her mystique.

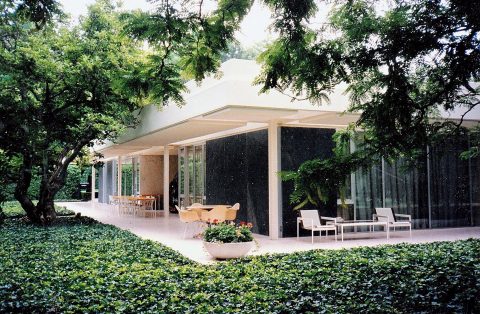

a new yorker born into an artistic family of ample means, aline took her first tour of european art and architecture at the age of 9. she graduated with honors from vassar, then quickly married and had two sons, but she also pursued graduate school. after a stint editing an art magazine, she was hired by the times. she was 38 when she interviewed saarinen. by then, she had cultivated a quality in herself she called “intelluptuous”—a combination of intelligence and voluptuousness that he clearly found irresistible. they married, she moved into his remodeled victorian farmhouse in bloomfield hills, and they had a baby named eames, for eero’s best friend, designer charles eames.

but domestic life didn’t curb the energetic aline from fulfilling her husband’s agenda, or her own. like a one-woman p.r. firm, she wrote eloquent letters and notes to writers and editors who were positioning saarinen at the forefront of contemporary culture throughout the ’50s—he was on a 1956 cover of time magazine. with her vivacious charm, she helped captivate the corporate chieftains, ambassadors, and university presidents who became saarinen’s clients, and traveled with him as far as australia (where he was the key jury member in selecting the design for the sydney opera house, which is very saarinen-esque, if you think about it). at home, aline hosted a parade of visitors—the eameses from california, alexander calder, buckminster fuller. when alone, the couple retired after dinner to a shared workroom, where she would critique his designs, while he pushed her to write, even making a chart to keep her on track with the manuscript for the proud possessors.

saarinen once told aline that she lived on “rabbit time” rather than the “elephant time” that architects lived on. but his life span, sadly, wasn’t elephantine: in 1961 he was diagnosed with a brain tumor and died a day after surgery. he was 51, an age when most architects are just reaching their prime. though she was shattered—and inundated by condolences from a who’s who of mourners—she turned quickly to burnishing his legacy. she helped consult on a half-hour cbs-tv special on saarinen, broadcast only two months after his death, and supplied material for a flood of articles and tributes. within a year, she’d produced the definitive book on his work. most important was her role in holding on to saarinen’s patrons.

most of the major buildings he designed were not finished at the time of his death, but she drew on her close relationships to reassure his clients that the other architects in his office could complete the work. “i think cbs would probably have dropped the ball and gone to another architect if aline hadn’t convinced bill paley and frank stanton [the company president] that we were ok,” recalls kevin roche, who worked with eero on design. “after all, we were completely unknown.” aline weighed in on the final selection of dark stone for cbs’s headquarters in new york and smoothed the firm’s way with najeeb halaby, head of the federal aviation agency, on the completion of dulles international airport. on the day of the dedication in 1962, she stood on the dais with halaby and president kennedy.

when the twa building—saarinen’s most romantic, exuberant design—opened the same year, the today show broadcast live from inside the terminal, with john chancellor and aline sitting side by side. she was beginning to become a familiar face; her easy eloquence made her a natural on the morning program. (her colleague barbara walters said of aline: “she was an intellectual without being pretentious.”)

later, president johnson, whom she counted as a friend, wanted to appoint her u.s. ambassador to finland. but she stayed in tv, at first covering art and culture, then reporting more broadly; she was at the tumultuous 1968 chicago democratic convention, in vietnam, and, ultimately, she headed the nbc bureau in paris. she was there only a year when she was diagnosed with cancer and died, in 1972, at 58. the fact that she’s little-known today is a shame. standing next to one of the giants of midcentury american culture, aline saarinen cast quite a shadow, too.

written by cathleen mcguigan via newsweek photo: tony vaccaro / courtesy eero saarinen collection-yale

university library

resources:

eero saarinen myspace

saarinen knoll

love & architecture